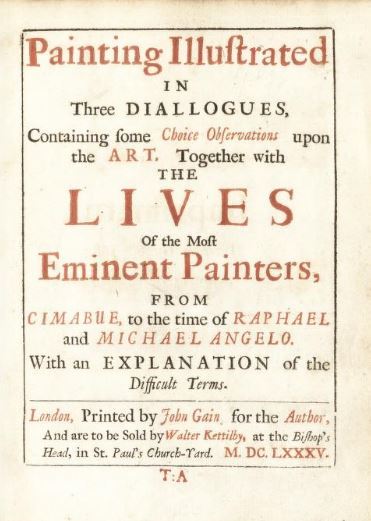

AGLIONBY, William, Painting Illustrated in Three Diallogues. Containing some Choice Observations upon the Art. Together with The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters From Cimabue, to the time of Raphael and Michael Angelo. With an Explanation of the Difficult Terms, London, John Gain, 1685.

L’écriture de cet ouvrage est dictée par le constat fait par Aglionby du manque d’intérêt pour les arts, et notamment pour la peinture d’histoire, en Angleterre, contrairement à d’autres pays européens – ce qu’il a pu constater durant ses divers séjours. Cette dénonciation apparaît en particulier dans la préface de Painting illustrated, où Aglionby affirme qu’aucun peintre d’histoire n’est né sur le sol anglais – John Evelyn, auteur anglais d’un texte sur l’art et traducteur de Fréart de Chambray, fait le même constat. Selon lui, cela provient de la préférence pour le portrait, mais aussi du fait que les personnes susceptibles de commander des œuvres d’art manquent de connaissances et ne peuvent donc pas encourager le genre « noble » qu’est la peinture d’histoire. Le but de son ouvrage est d’expliquer les principes généraux de ce genre pictural, mais aussi de familiariser les éventuels commanditaires à la peinture italienne. Pour ce faire, il fournit un glossaire expliquant des termes liés en particulier à la peinture d’histoire, tels que cartoon, drapery, figure, history ou encore model, comme le fit également Evelyn dans sa traduction de Fréart de Chambray. Il construit en outre son ouvrage sous la forme de trois dialogues entre un connaisseur de l’art, le traveler qui, après avoir voyagé, a acquis un certain nombre de connaissances en art, et un de ses amis, qui aimerait en apprendre davantage sur la peinture. Dans le premier dialogue, le traveller explique à son ami des termes et notions techniques. Il insiste par exemple sur la différence entre la peinture à l’huile, à la détrempe et la fresque. Le deuxième discours expose une histoire de la peinture de l’Antiquité jusqu’à leur époque, en s’attardant surtout sur des artistes italiens, même si certains peintres nordiques sont évoqués. Enfin, le dernier discours s’intéresse à la manière de bien juger un tableau. L’ouvrage contient également des Vies d’artistes italiens de la Renaissance (la première est celle de Cimabue et la dernière de Donatello) fondées sur onze Vite de Vasari – il s’agit de la première traduction en anglais de ce texte [2]. Tout au long de son texte, Aglionby insiste sur le fait que la peinture peut s’apprendre facilement et qu’il suffit d’avoir quelques connaissances. L’auteur se présente ainsi comme un virtuoso désireux de promouvoir la peinture d’histoire en Angleterre, en s’appuyant sur des exemples italiens en particulier [3].

Il est intéressant de noter qu’Aglionby utilise beaucoup l’italique dans ses dialogues. Il distingue ainsi les propos du voyageur de ceux de son ami, qui sont en écriture romaine. En outre, certains termes se distinguent dans les propos du voyageur en n’étant pas en italiques. De même, dans les paroles de l’ami, des termes apparaissent en italiques. Dans les deux cas, ces mots mis en valeur peuvent parfois être significatifs : il s’agit soit de noms d’artistes et de lieux, soit de termes liés à la peinture comme light, colours ou encore passion. Mais parfois, il s’agit d’un vocabulaire lié à la vie quotidienne plus qu’à la peinture, comme dans le cas de slaves, foundation ou gentlemen.

Aglionby se trouve néanmoins face à un problème : celui du manque de vocabulaire artistique en anglais. Pour contourner cela, il emploie alors des termes italiens, tels que morbidezza ou schizzo. Il tente en outre de traduire et d’adapter certains mots à la langue anglaise. À la place du terme italien attitudine, néanmoins mentionné, Aglionby utilise par exemple aptitude – terme évoqué avant lui par Evelyn dans sa traduction de Fréart. Il tente ainsi d’adapter le vocabulaire artistique à l’anglais, afin de le rendre davantage familier au lectorat de son pays.

Le texte d’Aglionby est influencé par la théorie continentale des arts, et notamment par le De Arte Graphica de Dufresnoy (1668). Il reprend par exemple la division de la peinture en trois parties, dessin, couleur et invention, que l’on retrouve chez ce dernier. Comme le notent certains historiens de l’art, tels B. Cowan, « Aglionby’s own writings on painting were more or less a reiteration of arguments made several decades earlier by the French writer Charles Du Fresnoy [4] ». Il semble évident que les séjours à l’étranger d’Aglionby ont eu un rôle fondamental sur sa conception de l’art. Néanmoins, selon C. Hanson, puis C. Good, même si Aglionby s’inspire fortement de la théorie française et italienne des arts, il demeure intéressant d’étudier la manière dont il s’approprie le texte de Dufresnoy et l’adapte pour un public anglais et non connaisseur [5]. En effet, Aglionby ne fournit pas une traduction littérale de Dufresnoy ou de son commentaire par de Piles, mais construit son texte sous forme de dialogue, ce qui lui permet d’apporter une touche personnelle. Il faut également replacer Painting illustrated dans le contexte de la Royal Society, institution, fondée en 1660, qui a pour but de promouvoir les sciences et le savoir en Angleterre. Elle valorise notamment les voyages et la diffusion des informations dans la sphère des Lettres. Parmi ses membres, on compte des collectionneurs et des commanditaires d’œuvres d’art [6]. Le but premier d’Aglionby est plutôt d’introduire le peuple anglais à la théorie continentale des arts plutôt que de faire une œuvre originale, ce que C. Good justifie par un manque de confiance de sa part [7]. Ce dernier ne serait ainsi pas prêt à mettre en place une véritable théorie de l’art anglaise, même si, de par le vocabulaire qu’il utilise, il apporte des éléments novateurs.

Élodie Cayuela

[1] C. Hanson, 2009, p. 95.

[2] Sur l'influence de Vasari chez Aglionby, voir F. Paknadel, 1978, p. 37-39.

[3] Sur les Virtuosi, voir B. Cowan, 2004.

[4] B. Cowan, 2004, p. 157, voir aussi L. Salerno, 1951, p. 250.

[5] C. Hanson, 2008, p. 18 et 99 ; C. Good, 2013, p. 97 ; F. Paknadel, 1978, p. 35-37.

[6] À ce propos, voir C. Hanson, 2008, p. 107 et B. Cowan, 2004, p. 170 et suivantes.

[7] C. Hanson, 2008, p. 99-103 ; C. Good, 2013, p. 101-102.

Dedication

William Cavendish, 4th Earl of Devonshire

Table des matières at n.p.

Glossaire at n.p.

Préface at n.p.

Dédicace(s) at n.p.

AGLIONBY, William, Painting Illustrated in Three Diallogues. Containing some Choice Observations upon the Art Together with the LIVES of the Most Eminent Painters From Cimabue, to the Time of Raphael and Michael Angelo. With an Explanation of the Difficult Terms, London, John Gain, 1686.

AGLIONBY, William, Choice Observations upon the Art of Painting. Together with Vasari's Lives Of the Most Eminent Painters, From Cimabue To the Time of Raphael and Michael Angelo. With an Explanation of the Difficult Terms, London, R. King, 1719.

AGLIONBY, William, Painting Illustrated in Three Diallogues, Portland, Collegium Graphicum, 1972.

CLARK, Georges, « Dr. William Aglionby », Notes and Queries, IX, 1921, p. 141-143.

SALERNO, Luigi, « Seventeenth-Century English Literature on Painting », Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 14/3-4, 1951, p. 234-258 [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/750341 consulté le 30/03/2018].

PAKNADEL, Félix, Critique et peinture en Angleterre de 1660 à 1770, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Provence, 1978.

GIBSON-WOOD, Carol, « Jonathan Richardson, Lord Somers's Collection of Drawings, and Early Art-Historical Writing in England », Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 52, 1989, p. 167-187 [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/751543 consulté le 30/03/2018].

BAXANDALL, Michael, « English Disegno », dans CHANEY, Edward et MACK, Peter (éd.), England and the Continental Renaissance. Essays in Honour of J. B. Trapp, Woodbridge - Rochester, The Boydell Press, 1990, p. 203-214.

COWAN, Brian, « An Open Elite: the Peculiarities of Connoisseurship in Early Modern England », Modern Intellectual History, 1/2, 2004, p. 151-183.

HANSON, Craig A., The English Virtuoso: Art, Medicine, and Antiquarianism in the Age of Empiricism, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

GOOD, Caroline Anne, “Lovers of Art”. Early English Literature on the Connoisseurship of Pictures, Thesis, University of York, 2013 [En ligne : http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/5694/1/Caroline%20Good%20'Lovers%20of%20Art'%20PhD%20Thesis.pdf consulté le 11/07/2016].

FILTERS

QUOTATIONS

Providence yet kinder, gave us two Arts, which might express the very Lines of the Face, the Air of the Countenance, and in it a great part of the Mind of all those whom they should undertake to Represent ; and these are, Sculpture and Painting.

Michael Angelo, the famousest Sculptor of these Modern Ages, looking one day earnestly upon a Statue of St. Mark made by Donatello, after having long admired it, said at last, That if Saint Mark were like that Statue, he would have believed his Gospel upon his Physionomy, for it was the honestest Face that ever was made. ’Tis hard to say, whether he commended the Artist, the Saint, or the Art it self most by this Expression : But this Inference we may make from it, That if the Faces of Heroes do express the Greatness of their Minds, those Arts which perpetuate their Memory that way, are the truest of all Records.

I shall not undertake to determine here, which of these two Arts [ndr : la peinture et la sculpture] deserves our Admiration most : [...] But this I may say in favour of the Art of Painting, whose praises I am now to Celebrate, That it certainly is of a greater Extent than Sculpture, and has an Infiniter Latitude to delight us withal. [...] And from this Idæa of the Art, we may naturally derive a Consequence of the Admiration and Esteem due by us to the Artist ; he who at the same time is both Painter, Poet, Historian, Architect, Anatomist, Mathematician, and Naturalist ; he Records the Truth, Adorns the Fable, Pleases the Fancy, Recreates the Eye, Touches the Soul ; and in a word, entertains you with Silent Instructions, which are neither guilty of Flattery, nor Satyr ; and which you may either give over, or repeat with new Delight as often as you please.

If these Qualities do not sufficiently recommend the Owner of them to our Esteem, I know not what can ; and yet by a strange Fatality, we name the word Painter, without reflecting upon his Art, and most dis-ingeniously, seem to place him among the Mechanicks, who has the best Title to all the Liberal Arts.

I shall not undertake to determine here, which of these two Arts [ndr : la peinture et la sculpture] deserves our Admiration most : The one, makes Marble-Stone and Brass soft and tender : the other, by a strange sort of Inchantment, makes a little Cloth and Colours show Living Figures, that upon a flat Superficies seem Round, and deceives the Eye into a Belief of Solids, while there is nothing but Lights and Shadows there : But this I may say in favour of the Art of Painting, whose praises I am now to Celebrate, That it certainly is of a greater Extent than Sculpture, and has an Infiniter Latitude to delight us withal.

To see in one Piece the Beauty of the Heavens, the Verdant Glory of the Earth, the Order and Symmetry of Pallaces and Temples ; the Softness, Warmth, Strength, and Tenderness of Naked Figures, the Glorious Colours of Draperies and Dresses of all kinds, the Liveliness of Animals ; and above all, the Expression of our Passions, Customs, Manners, Rites, Ceremonies, Sacred and Prophane : All this, I say, upon a piece of portative Cloth, easily carried, and as easily placed, is a Charm ; which no other Art can equal.

Air.

Is properly taken for the Look of a Figure, and is used in this Manner, The Air of the Heads of Young Women, or Grave Men, &c.

Aptitude.

It come from the Italian word Attitudine, and means the posture and action that any Figure is represented in.

Il est à noter qu'Aglionby n'emploie pas le terme anglais Attitude, mais celui d'Aptitude.

Conceptual field(s)

Cartoon.

It is taken for a Design made of many Sheets of Paper pasted together ; in which the whole Story to be painted in Fresco, is all drawn exactly, as it must be upon the Wall in Colours : Great Painters never painting in Fresco, but they make Cartoons first.

Chiaro-Scuro.

It is taken in two Senses : first, Painting in Chiaro-Scuro, is meant, when there are only two Colours employed. Secondly, It is taken for the disposing of the Lights and Shadows Skilfully ; as when we say, A Painter understands well the Chiaro-Scuro.

Le terme painting est ici compris dans un sens large, comprenant le dessin.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Contour.

The Contour of a Body, are the Lines that environ it, and make the Superficies of it.

Design.

Has two Significations : First, As a part of Painting, it signifies the just Measures, Proportions, and Outvvard Forms that a Body, imitated from Nature, ought to havt. Secondly, It signifies the whole Composition of a piece of Painting ; as when we say, There is great Design in such a Piece.

Conceptual field(s)

Distemper

A sort of Painting that implys the Colours mingled with Gumm. And the difference between that and Miniature, is than the one only uses the Point of the Pencil, the other gives the Pencil its whole Liberty.

Drapery.

Is a General Word for all sorts of Cloathing, with which Figures are Adorned : So we say, Such a Painter disposes well the Foldings of his Drapery.

Figure.

Though this word be very General, and may be taken for any painted Object ; yet it is in Painting, generally taken for Humane Figures.

Fresco.

A Sort of Painting, where the Colours are applyed upon fresh Mortar, that they may Incorporate with the Lime and Sand.

Grotesk.

Is properly the Painting that is found under Ground in the Ruines of Rome ; but it signifies more commonly a sort of Painting that expresses odd Figures of Animals, Birds, Flowers, Leaves, or such like, mingled together in one Ornament or Border.

Gruppo.

Is a Knot of Figures together, either in the middle or sides of a piece of Painting. So Carrache would not allow above three Gruppos, nor above twelve Figures for any Piece.

History.

History-Painting is an Assembling of many Figures in one Piece, to Represent any Action of Life, whether True or Fabulous, accompanied with all its Ornaments of Landskip and Perspective.

Manner.

We call Manner the Habit of a Painter, not only of his Hand, but of his Mind ; that is, his way of expressing himself in the three principal Parts of Painting, Design, Colouring, and Invention ; it answers to Stile in Authors ; for a Painter is known by his Manner, as an Author by his Stile, or a Man’s Hand by his Writing.

Model.

Is any Object that a Painter works by, either after Nature, or otherwise ; but most commonly it signifies that which Sculptors, Painters, and Architects make to Govern themselves by in their Design.

Conceptual field(s)

Nudity.

Signifies properly any Naked Figure of Man or Woman ; but most commonly of Woman ; as when we say, ’Tis a Nudity, we mean the Figure of a Naked Woman.

Print.

Is the Impression of a Graven or Wooden Plate upon Paper or Silk, Representing some Piece that it has been Graved after.

Conceptual field(s)

Relievo.

Is properly any Embossed Sculpture that rises from a flat Superficies. It is said likewise of Painting, that it has a great Relievo, when it is strong, and that the Figures appear round, and as it were, out of the Piece.

Shortning.

Is, when a Figure seems of greater quantity than really it is ; as, if it seems to be three foot long, when it is but one : Some call it Fore-Shortning.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Schizzo.

Is the first Design or Attempt of a Painter to Express his Thoughts upon any Subject. The Schizzos are ordinarily reduced into Cartoons in Fresco Painting, or Copyed and Enlarged in Oyl-Painting.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

The Art of Painting, is the Art of Representing any Object by Lines drawn upon a flat Superficies, which Lines are afterwards covered with Colours, and those Colours applied with a certain just distribution of Lights and Shades, with a regard to the Rules of Symetry and Perspective ; the whole producing a Likeness, or true Idæa of the Subject intended.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

The Art of Painting, is the Art of Representing any Object by Lines drawn upon a flat Superficies, which Lines are afterwards covered with Colours, and those Colours applied with a certain just distribution of Lights and Shades, with a regard to the Rules of Symetry and Perspective ; the whole producing a Likeness, or true Idæa of the Subject intended.

Friend,

This seems to embrace a great deal ; for the words Symetry and Perspective, imply a knowledg in Proportions and Distances, and that supposes Geometry, in some measure, and Opticks, all which require much Time to Study them, and so I am still involved in perplexities of Art.

Traveller,

It is true, that those Words seem to require some Knowledg of those Arts in the Painter, but much less in the Spectator ; for we may easily guess, whether Symetry be observed, if, for Example, in a Humane Body, we see nothing out of Proportion ; as if an Arm or a Leg be not too long or short for its Posture, or if the Posture its self be such as Nature allows of :

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

The Art of Painting, is the Art of Representing any Object by Lines drawn upon a flat Superficies, which Lines are afterwards covered with Colours, and those Colours applied with a certain just distribution of Lights and Shades, with a regard to the Rules of Symetry and Perspective ; the whole producing a Likeness, or true Idæa of the Subject intended.

Friend,

This seems to embrace a great deal ; for the words Symetry and Perspective, imply a knowledg in Proportions and Distances, and that supposes Geometry, in some measure, and Opticks, all which require much Time to Study them, and so I am still involved in perplexities of Art.

Traveller,

It is true, that those Words seem to require some Knowledg of those Arts in the Painter, but much less in the Spectator ; for we may easily guess, whether Symetry be observed, if, for Example, in a Humane Body, we see nothing out of Proportion ; as if an Arm or a Leg be not too long or short for its Posture, or if the Posture its self be such as Nature allows of : And for Perspective, we have only to observe whether the Objects represented to be at a distance, do lessen in the Picture, as they would do naturally to the Eye, at such and such distances ; thus you see these are but small Difficulties.

Traveller,

Design is the Expressing with a Pen, or Pencil, or other Instrument, the Likeness of any Object by its out Lines, or Contours ; and he that Understands and Mannages well these first Lines, working after Nature still, and using extream Diligence, and skill may with Practice and Judgment, arrive to an Excellency in the Art.

Friend,

Me thinks that should be no difficult Matter, for we see many whose Inclination carys them to Draw any thing they see, and they perform it with ease.

Traveller,

I grant you, Inclination goes a great way in disposing the Hand, but a strong Imagination only, will not carry a Painter through ; For when he compares his Work to Nature, he will soon find, that great Judgment is requisite, as well as a Lively Fancy ; and particularly when he comes to place many Objects together in one Piece or Story, which are all to have a just relation to one another. There he will find that not only the habit of the Hand but the strength of the Mind is requisite ; therefore all the Eminent Painters that ever were, spent more time in Designing after the Life, and after the Statues of the Antients, then ever did in learning how to colour their Works ; that so they might be Masters of Design, and be able to place readily every Object in its true situation.

Friend,

Now you talk of Nature and Statues, I have heard Painters blam’d for working after both.

Traveller,

It is very true, and justly ; but less for working after Nature than otherwise. Caravaggio a famous Painter is blam’d for having meerly imitated Nature as he found her, without any correction of Forms. And Perugin, another Painter is blam’d for having wrought so much after Statues, that his Works never had that lively easiness which accompanies Nature ; and of this fault Raphael his Scholar was a long time guilty, till he Reform’d it by imitating Nature.

CARAVAGGIO (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio)

PERUGINO, Pietro (Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

Design is the Expressing with a Pen, or Pencil, or other Instrument, the Likeness of any Object by its out Lines, or Contours ; and he that Understands and Mannages well these first Lines, working after Nature still, and using extream Diligence, and skill may with Practice and Judgment, arrive to an Excellency in the Art.

Friend,

Me thinks that should be no difficult Matter, for we see many whose Inclination carys them to Draw any thing they see, and they perform it with ease.

Traveller,

I grant you, Inclination goes a great way in disposing the Hand, but a strong Imagination only, will not carry a Painter through ; For when he compares his Work to Nature, he will soon find, that great Judgment is requisite, as well as a Lively Fancy ; and particularly when he comes to place many Objects together in one Piece or Story, which are all to have a just relation to one another. There he will find that not only the habit of the Hand but the strength of the Mind is requisite ; therefore all the Eminent Painters that ever were, spent more time in Designing after the Life, and after the Statues of the Antients, then ever did in learning how to colour their Works ; that so they might be Masters of Design, and be able to place readily every Object in its true situation.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

Design is the Expressing with a Pen, or Pencil, or other Instrument, the Likeness of any Object by its out Lines, or Contours ; and he that Understands and Mannages well these first Lines, working after Nature still, and using extream Diligence, and skill may with Practice and Judgment, arrive to an Excellency in the Art.

Friend,

Me thinks that should be no difficult Matter, for we see many whose Inclination carys them to Draw any thing they see, and they perform it with ease.

Traveller,

I grant you, Inclination goes a great way in disposing the Hand, but a strong Imagination only, will not carry a Painter through ; For when he compares his Work to Nature, he will soon find, that great Judgment is requisite, as well as a Lively Fancy ; and particularly when he comes to place many Objects together in one Piece or Story, which are all to have a just relation to one another. There he will find that not only the habit of the Hand but the strength of the Mind is requisite ; therefore all the Eminent Painters that ever were, spent more time in Designing after the Life, and after the Statues of the Antients, then ever did in learning how to colour their Works ; that so they might be Masters of Design, and be able to place readily every Object in its true situation.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

Design is the Expressing with a Pen, or Pencil, or other Instrument, the Likeness of any Object by its out Lines, or Contours ; and he that Understands and Mannages well these first Lines, working after Nature still, and using extream Diligence, and skill may with Practice and Judgment, arrive to an Excellency in the Art.

Friend,

Me thinks that should be no difficult Matter, for we see many whose Inclination carys them to Draw any thing they see, and they perform it with ease.

Traveller,

I grant you, Inclination goes a great way in disposing the Hand, but a strong Imagination only, will not carry a Painter through ; For when he compares his Work to Nature, he will soon find, that great Judgment is requisite, as well as a Lively Fancy ; and particularly when he comes to place many Objects together in one Piece or Story, which are all to have a just relation to one another. There he will find that not only the habit of the Hand but the strength of the Mind is requisite ; therefore all the Eminent Painters that ever were, spent more time in Designing after the Life, and after the Statues of the Antients, then ever did in learning how to colour their Works ; that so they might be Masters of Design, and be able to place readily every Object in its true situation.

Friend,

Now you talk of Nature and Statues, I have heard Painters blam’d for working after both.

Traveller,

It is very true, and justly ; but less for working after Nature than otherwise. Caravaggio a famous Painter is blam’d for having meerly imitated Nature as he found her, without any correction of Forms. And Perugin, another Painter is blam’d for having wrought so much after Statues, that his Works never had that lively easiness which accompanies Nature ; and of this fault Raphael his Scholar was a long time guilty, till he Reform’d it by imitating Nature.

Friend,

How is it possible to erre in imitating Nature ?

Traveller,

Though Nature be the Rule, yet Art has the Priviledge of Perfecting it ; for you must know that there are few Objects made naturally so entirely Beautiful as they might be, no one Man or Woman possesses all the Advantages of Feature, Proportion and Colour due to each Sence. Therefore the Antients, when they had any Great Work to do, upon which they would Value themselves did use to take several of the Beautifullest Objects they designed to Paint, and out of each of them, Draw what was most Perfect to make up One exquisite Figure ; Thus Zeuxis being imployed by the Inhabitants of Crotona, a City of Calabria, to make for their Temple of Juno, a Female Figure, Naked ; He desired the Liberty of seeing their Hansomest Virgins, out of whom he chose Five, from whose several Excellencies he fram’d a most Perfect Figure, both in Features, Shape and Colouring, calling it Helena.

CARAVAGGIO (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio)

PERUGINO, Pietro (Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

ZEUXIS

Expression "Working after nature"

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

I grant you, Inclination goes a great way in disposing the Hand, but a strong Imagination only, will not carry a Painter through ; For when he compares his Work to Nature, he will soon find, that great Judgment is requisite, as well as a Lively Fancy ; and particularly when he comes to place many Objects together in one Piece or Story, which are all to have a just relation to one another. There he will find that not only the habit of the Hand but the strength of the Mind is requisite ; therefore all the Eminent Painters that ever were, spent more time in Designing after the Life, and after the Statues of the Antients, then ever did in learning how to colour their Works ; that so they might be Masters of Design, and be able to place readily every Object in its true situation.

Friend,

Now you talk of Nature and Statues, I have heard Painters blam’d for working after both.

Traveller,

It is very true, and justly ; but less for working after Nature than otherwise. Caravaggio a famous Painter is blam’d for having meerly imitated Nature as he found her, without any correction of Forms. And Perugin, another Painter is blam’d for having wrought so much after Statues, that his Works never had that lively easiness which accompanies Nature ; and of this fault Raphael his Scholar was a long time guilty, till he Reform’d it by imitating Nature.

Friend,

How is it possible to erre in imitating Nature ?

Traveller,

Though Nature be the Rule, yet Art has the Priviledge of Perfecting it ; for you must know that there are few Objects made naturally so entirely Beautiful as they might be, no one Man or Woman possesses all the Advantages of Feature, Proportion and Colour due to each Sence. Therefore the Antients, when they had any Great Work to do, upon which they would Value themselves did use to take several of the Beautifullest Objects they designed to Paint, and out of each of them, Draw what was most Perfect to make up One exquisite Figure ; Thus Zeuxis being imployed by the Inhabitants of Crotona, a City of Calabria, to make for their Temple of Juno, a Female Figure, Naked ; He desired the Liberty of seeing their Hansomest Virgins, out of whom he chose Five, from whose several Excellencies he fram’d a most Perfect Figure, both in Features, Shape and Colouring, calling it Helena.

Conceptual field(s)

Though Nature be the Rule, yet Art has the Priviledge of Perfecting it ; for you must know that there are few Objects made naturally so entirely Beautiful as they might be, no one Man or Woman possesses all the Advantages of Feature, Proportion and Colour due to each Sence. Therefore the Antients, when they had any Great Work to do, upon which they would Value themselves did use to take several of the Beautifullest Objects they designed to Paint, and out of each of them, Draw what was most Perfect to make up One exquisite Figure ; Thus Zeuxis being imployed by the Inhabitants of Crotona, a City of Calabria, to make for their Temple of Juno, a Female Figure, Naked ; He desired the Liberty of seeing their Hansomest Virgins, out of whom he chose Five, from whose several Excellencies he fram’d a most Perfect Figure, both in Features, Shape and Colouring, calling it Helena.

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

Would you have a Painter study nothing but Humane Figures ?

Traveller,

That being the most difficult in his Art, he must chiefly Study it ; But because no Story can be well Represented without Circumstances, therefore he must Learn to Design every thing, as Trees, Houses, Water, Clothes, Animals, and in short, all that falls under the notion of Visible Objects ;

Traveller.

The Shortning of a Figure, is the making it appear of more Quantity, than really it is ; the Figure having neither the Length nor Depth that it shows, but by the help of the Lights and Shades, and judicious mannaging of the Out-lines, it appears what it is not ; and this is much used in Painting of Ceelings and Roofs, where the Figures being above the Eye, must be most of them Shortned, to appear in their natural Situation. And it is a thing, upon which great Painters have Valued themselves, as supposing a great Knowledg of the Muscles and Bones of the Humane Body, and a great Skill in Designing. Michael Angelo, amongst the Modern Painters, is the greatest Master in that kind.

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

When a Painter has acquired any Excellency in Desinging, readily and strongly ; What has he to do next ?

Traveller,

That is not half his Work, for then he must begin to mannage his Colours, it being particularly by them, that he is to express the greatness of his Art. ’Tis they that give, as it were, Life and Soul to all that he does ; without them, his Lines will be but Lines that are flat, and without a Body, but the addition of Colours makes that appear round ; and as it were out of the Picture, which else would be plain and dull. ’Tis they that must deceive the Eye, to the degree, to make Flesh appear warm and soft, and to give an Air of Life, so as his Picture may seem almost to Breath and Move.

Friend,

Did ever any Painter arrive to that Perfection you mention ?

Traveller,

Yes, several, both of the Antient and Modern Painters. Zeuxis Painted Grapes, so that the Birds flew at them to eat them. Apelles drew Horses to such a likeness, that upon setting them before live Horses, the Live ones Neighed, and began to kick at them, as being of their own kind.

Friend,

When a Painter has acquired any Excellency in Desinging, readily and strongly ; What has he to do next ?

Traveller,

That is not half his Work, for then he must begin to mannage his Colours, it being particularly by them, that he is to express the greatness of his Art. ’Tis they that give, as it were, Life and Soul to all that he does ; without them, his Lines will be but Lines that are flat, and without a Body, but the addition of Colours makes that appear round ; and as it were out of the Picture, which else would be plain and dull. ’Tis they that must deceive the Eye, to the degree, to make Flesh appear warm and soft, and to give an Air of Life, so as his Picture may seem almost to Breath and Move. [...] Friend,

Wherein particularly lies the Art of Colouring ?

Traveller.

Beside the Mixture of Colours, such as may answer the Painter’s Aim, it lies in a certain Contention, as I may call it, between the Light and the Shades, which by the means of Colours, are brought to Unite with each other ; and so to give that Roundness to the Figures, which the Italians call Relievo, and for which we have no other Name : In this, if the Shadows are too strong, the Piece is harsh and hard, if too weak, and there be too much Light, ’tis flat.

Italiens (les)

Conceptual field(s)

Italiens (les)

Conceptual field(s)

Italiens (les)

Conceptual field(s)

Italiens (les)

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

When a Painter has acquired any Excellency in Desinging, readily and strongly ; What has he to do next ?

Traveller,

That is not half his Work, for then he must begin to mannage his Colours, it being particularly by them, that he is to express the greatness of his Art. ’Tis they that give, as it were, Life and Soul to all that he does ; without them, his Lines will be but Lines that are flat, and without a Body, but the addition of Colours makes that appear round ; and as it were out of the Picture, which else would be plain and dull. ’Tis they that must deceive the Eye, to the degree, to make Flesh appear warm and soft, and to give an Air of Life, so as his Picture may seem almost to Breath and Move.

Friend,

When a Painter has acquired any Excellency in Desinging, readily and strongly ; What has he to do next ?

Traveller,

That is not half his Work, for then he must begin to mannage his Colours, it being particularly by them, that he is to express the greatness of his Art. ’Tis they that give, as it were, Life and Soul to all that he does ; without them, his Lines will be but Lines that are flat, and without a Body, but the addition of Colours makes that appear round ; and as it were out of the Picture, which else would be plain and dull. ’Tis they that must deceive the Eye, to the degree, to make Flesh appear warm and soft, and to give an Air of Life, so as his Picture may seem almost to Breath and Move.

Friend,

Did ever any Painter arrive to that Perfection you mention ?

Traveller,

Yes, several, both of the Antient and Modern Painters. Zeuxis Painted Grapes, so that the Birds flew at them to eat them. Apelles drew Horses to such a likeness, that upon setting them before live Horses, the Live ones Neighed, and began to kick at them, as being of their own kind. And amongst the Modern Painters, Hannibal Carache, relates to himself, That going to see Bassano at Venice, he went to take a Book off a Shelf, and found it to be the Picture of one, so lively done, that he who was a Great Painter, was deceived by it. The Flesh of Raphael’s Pictures are so Natural, that this seems to be Alive. And so do Titians Pictures, who was the Greatest Master for Colouring that ever was, having attained to imitate Humane Bodies in all the softness of Flesh, and beauty of Skin and Complexion.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

Wherein particularly lies the Art of Colouring ?

Traveller.

Beside the Mixture of Colours, such as may answer the Painter’s Aim, it lies in a certain Contention, as I may call it, between the Light and the Shades, which by the means of Colours, are brought to Unite with each other ; [...] Friend,

Is there any Rule for that ?

Traveller,

Some Observations there are, as those Figures which are placed on the foremost Ground, or next the Eye, ought to have the greatest Strength, both in their Lights and Shadows, and Cloathed with a lively Drapery ; Observing, that as they lessen by distance, and are behind, to give both the Flesh and the Drapery more faint and obscure Colouring. And this is called an Union in Painting, which makes up an Harmony to the Eye, and causes the Whole to appear one, and not two or three Pictures.

Friend,

Wherein particularly lies the Art of Colouring ?

Traveller.

Beside the Mixture of Colours, such as may answer the Painter’s Aim, it lies in a certain Contention, as I may call it, between the Light and the Shades, which by the means of Colours, are brought to Unite with each other ; and so to give that Roundness to the Figures, which the Italians call Relievo, and for which we have no other Name : In this, if the Shadows are too strong, the Piece is harsh and hard, if too weak, and there be too much Light, ’tis flat.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

Wherein particularly lies the Art of Colouring ?

Traveller.

Beside the Mixture of Colours, such as may answer the Painter’s Aim, it lies in a certain Contention, as I may call it, between the Light and the Shades, which by the means of Colours, are brought to Unite with each other ; and so to give that Roundness to the Figures, which the Italians call Relievo, and for which we have no other Name : In this, if the Shadows are too strong, the Piece is harsh and hard, if too weak, and there be too much Light, ’tis flat. I, for my part, should like a Colouring rather something Brown, but clear, than a bright gay one : But particularly, I think, that those fine Coral Lips, and Cherry Cheeks, are to be Banished, as being far from Flesh and Blood. ’Tis true, the Skins, or Complexions must vary, according to the Age and Sex of the Person ; An Old Woman requiring another Colouring than a fresh Young one. But the Painters must particularly take Care, that there be nothing harsh to offend the Eye, as that neither the Contours, or Out-Lines, be too strongly Terminated, nor the Shadows too hard, nor such Colours placed by one another as do not agree.

Friend,

Is there any Rule for that ?

Traveller,

Some Observations there are, as those Figures which are placed on the foremost Ground, or next the Eye, ought to have the greatest Strength, both in their Lights and Shadows, and Cloathed with a lively Drapery ; Observing, that as they lessen by distance, and are behind, to give both the Flesh and the Drapery more faint and obscure Colouring. And this is called an Union in Painting, which makes up an Harmony to the Eye, and causes the Whole to appear one, and not two or three Pictures.

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

Wherein particularly lies the Art of Colouring ?

Traveller.

Beside the Mixture of Colours, such as may answer the Painter’s Aim, it lies in a certain Contention, as I may call it, between the Light and the Shades, which by the means of Colours, are brought to Unite with each other ; and so to give that Roundness to the Figures, which the Italians call Relievo, and for which we have no other Name : In this, if the Shadows are too strong, the Piece is harsh and hard, if too weak, and there be too much Light, ’tis flat. I, for my part, should like a Colouring rather something Brown, but clear, than a bright gay one : [...] But the Painters must particularly take Care, that there be nothing harsh to offend the Eye, as that neither the Contours, or Out-Lines, be too strongly Terminated, nor the Shadows too hard, nor such Colours placed by one another as do not agree.

Friend,

Is there any Rule for that ?

Traveller,

Some Observations there are, as those Figures which are placed on the foremost Ground, or next the Eye, ought to have the greatest Strength, both in their Lights and Shadows, and Cloathed with a lively Drapery ; Observing, that as they lessen by distance, and are behind, to give both the Flesh and the Drapery more faint and obscure Colouring. And this is called an Union in Painting, which makes up an Harmony to the Eye, and causes the Whole to appear one, and not two or three Pictures.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

Wherein particularly lies the Art of Colouring ?

Traveller.

Beside the Mixture of Colours, such as may answer the Painter’s Aim, it lies in a certain Contention, as I may call it, between the Light and the Shades, which by the means of Colours, are brought to Unite with each other ; and so to give that Roundness to the Figures, which the Italians call Relievo, and for which we have no other Name : In this, if the Shadows are too strong, the Piece is harsh and hard, if too weak, and there be too much Light, ’tis flat. I, for my part, should like a Colouring rather something Brown, but clear, than a bright gay one : But particularly, I think, that those fine Coral Lips, and Cherry Cheeks, are to be Banished, as being far from Flesh and Blood.

Friend,

Wherein particularly lies the Art of Colouring ?

Traveller.

Beside the Mixture of Colours, such as may answer the Painter’s Aim, it lies in a certain Contention, as I may call it, between the Light and the Shades, which by the means of Colours, are brought to Unite with each other ; and so to give that Roundness to the Figures, which the Italians call Relievo, and for which we have no other Name : In this, if the Shadows are too strong, the Piece is harsh and hard, if too weak, and there be too much Light, ’tis flat. I, for my part, should like a Colouring rather something Brown, but clear, than a bright gay one : But particularly, I think, that those fine Coral Lips, and Cherry Cheeks, are to be Banished, as being far from Flesh and Blood. ’Tis true, the Skins, or Complexions must vary, according to the Age and Sex of the Person ; An Old Woman requiring another Colouring than a fresh Young one. But the Painters must particularly take Care, that there be nothing harsh to offend the Eye, as that neither the Contours, or Out-Lines, be too strongly Terminated, nor the Shadows too hard, nor such Colours placed by one another as do not agree.

Traveller,

Some Observations there are, as those Figures which are placed on the foremost Ground, or next the Eye, ought to have the greatest Strength, both in their Lights and Shadows, and Cloathed with a lively Drapery ; Observing, that as they lessen by distance, and are behind, to give both the Flesh and the Drapery more faint and obscure Colouring. And this is called an Union in Painting, which makes up an Harmony to the Eye, and causes the Whole to appear one, and not two or three Pictures.

Traveller.

There is a thing which the Italians call Morbidezza ; The meaning of which word, is to Express the Softness, and tender Liveliness of Flesh and Blood, so as the Eye may almost invite the Hand to touch and feel it, as if it were Alive ; and this is the hardest thing to Compass in the whole Art of Painting. And ‘tis in this particular, that Titian, Corregio, and amongst the more Modern, Rubens, and Vandike, do Excel.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller.

There is a thing which the Italians call Morbidezza ; The meaning of which word, is to Express the Softness, and tender Liveliness of Flesh and Blood, so as the Eye may almost invite the Hand to touch and feel it, as if it were Alive ; and this is the hardest thing to Compass in the whole Art of Painting. And ‘tis in this particular, that Titian, Corregio, and amongst the more Modern, Rubens, and Vandike, do Excel.

Friend.

I have heard, that in some Pictures of Raphael, the very Gloss of Damask, and the Softness of Velvet, with the Lustre of Gold, are so Expressed, that you would take them to be Real, and not Painted : Is not that as hard to do, as to imitate Flesh ?

Traveller.

No : Because those things are but the stil Life, whereas there is a Spirit in Flesh and Blood, which is hard to Represent. But a good Painter must know how to do those Things you mention, and many more : As for Example, He must know how to Imitate the Darkness of Night, the Brightness of Day, the Shining and Glittering of Armour ; the Greenness of Trees, the Dryness of Rocks. In a word, All Fruits, Flowers, Animals, Buildings, so as that they all appear Natural and Pleasing to the Eye.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller.

There is a thing which the Italians call Morbidezza ; The meaning of which word, is to Express the Softness, and tender Liveliness of Flesh and Blood, so as the Eye may almost invite the Hand to touch and feel it, as if it were Alive ; and this is the hardest thing to Compass in the whole Art of Painting. And ‘tis in this particular, that Titian, Corregio, and amongst the more Modern, Rubens, and Vandike, do Excel.

Friend.

I have heard, that in some Pictures of Raphael, the very Gloss of Damask, and the Softness of Velvet, with the Lustre of Gold, are so Expressed, that you would take them to be Real, and not Painted : Is not that as hard to do, as to imitate Flesh ?

Traveller.

No : Because those things are but the stil Life, whereas there is a Spirit in Flesh and Blood, which is hard to Represent. But a good Painter must know how to do those Things you mention, and many more : As for Example, He must know how to Imitate the Darkness of Night, the Brightness of Day, the Shining and Glittering of Armour ; the Greenness of Trees, the Dryness of Rocks. In a word, All Fruits, Flowers, Animals, Buildings, so as that they all appear Natural and Pleasing to the Eye.

Traveller.

There is a thing which the Italians call Morbidezza ; The meaning of which word, is to Express the Softness, and tender Liveliness of Flesh and Blood, so as the Eye may almost invite the Hand to touch and feel it, as if it were Alive ; and this is the hardest thing to Compass in the whole Art of Painting. And ‘tis in this particular, that Titian, Corregio, and amongst the more Modern, Rubens, and Vandike, do Excel.

Friend.

I have heard, that in some Pictures of Raphael, the very Gloss of Damask, and the Softness of Velvet, with the Lustre of Gold, are so Expressed, that you would take them to be Real, and not Painted : Is not that as hard to do, as to imitate Flesh ?

Traveller.

No : Because those things are but the stil Life, whereas there is a Spirit in Flesh and Blood, which is hard to Represent. But a good Painter must know how to do those Things you mention, and many more : As for Example, He must know how to Imitate the Darkness of Night, the Brightness of Day, the Shining and Glittering of Armour ; the Greenness of Trees, the Dryness of Rocks. In a word, All Fruits, Flowers, Animals, Buildings, so as that they all appear Natural and Pleasing to the Eye. And he must not think as some do, that the force of Colouring consists in imploying of fine Colours, as fine lacks Ultra Marine Greens, &c. For these indeed, are fine before they are wrought, but the Painter’s Skill is to work them judiciously, and with convenience to his Subject.

Friend.

I have heard, that in some Pictures of Raphael, the very Gloss of Damask, and the Softness of Velvet, with the Lustre of Gold, are so Expressed, that you would take them to be Real, and not Painted : Is not that as hard to do, as to imitate Flesh ?

Traveller.

No : Because those things are but the stil Life, whereas there is a Spirit in Flesh and Blood, which is hard to Represent. But a good Painter must know how to do those Things you mention, and many more : As for Example, He must know how to Imitate the Darkness of Night, the Brightness of Day, the Shining and Glittering of Armour ; the Greenness of Trees, the Dryness of Rocks. In a word, All Fruits, Flowers, Animals, Buildings, so as that they all appear Natural and Pleasing to the Eye.

Friend.

I have heard, that in some Pictures of Raphael, the very Gloss of Damask, and the Softness of Velvet, with the Lustre of Gold, are so Expressed, that you would take them to be Real, and not Painted : Is not that as hard to do, as to imitate Flesh ?

Traveller.

No : Because those things are but the stil Life, whereas there is a Spirit in Flesh and Blood, which is hard to Represent. But a good Painter must know how to do those Things you mention, and many more : As for Example, He must know how to Imitate the Darkness of Night, the Brightness of Day, the Shining and Glittering of Armour ; the Greenness of Trees, the Dryness of Rocks. In a word, All Fruits, Flowers, Animals, Buildings, so as that they all appear Natural and Pleasing to the Eye. And he must not think as some do, that the force of Colouring consists in imploying of fine Colours, as fine lacks Ultra Marine Greens, &c. For these indeed, are fine before they are wrought, but the Painter’s Skill is to work them judiciously, and with convenience to his Subject.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

I have heard Painters blamed for Finishing their Pieces too much : How can that be ?

Traveller.

Very well : For an over Diligence in that kind, may come to make the Picture look too like a Picture, and loose the freedom of Nature. And it was in this, that Protogenes, who was, it may be, Superiour to Apelles, in every part of Painting ; besides, was nevertheless Outdone by him, because Protogenes could hardly ever give over Finishing a Piece. Whereas Apelles knew, when he had wrought so much as would answer the Eye of the Spectator, and preserve the Natural.

Friend,

I have heard Painters blamed for Finishing their Pieces too much : How can that be ?

Traveller.

Very well : For an over Diligence in that kind, may come to make the Picture look too like a Picture, and loose the freedom of Nature. And it was in this, that Protogenes, who was, it may be, Superiour to Apelles, in every part of Painting ; besides, was nevertheless Outdone by him, because Protogenes could hardly ever give over Finishing a Piece. Whereas Apelles knew, when he had wrought so much as would answer the Eye of the Spectator, and preserve the Natural. This the Italians call, Working A la pittoresk, that is Boldly, and according to the first Incitation of a Painters Genius. But this requires a strong Judgment, or else it will appear to the Judicious, meer Dawbing.

Traveller,

You must know, that the Italians have a Way of Painting their Pallaces, both within and without, upon the bear Walls, and before Oyl Painting came up, most Masters wrought that Way ; and it is the most Masterly of all the ways of Painting, because it is done upon a Wall newly Plaistered, and you must Plaister no more, than what you can do in a Day ; the Colours being to Incorporate with the Mortar, and dry with it, and it cannot be Touched over again, as all other Ways of Painting may : This is that they call Painting in Fresco.

Friend,

This must require a very Dexterous and quick Hand.

Traveller.

Yes, and a good Judgment too ; for the Colours will show otherwise when they are Dry, than they did when they were Wet : Therefore there is great Practice required in Mannaging them, but then this Way makes amends for its Difficulties ; for the longer it stands, it acquires still more Beauty and Union, it resisting both Wind and Rain.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

Painting in Distemper, is when either the Wall or Board you Paint upon, is prepared with a certain Paste or Plaister, and then as you Work, you temper your Colours still with a Liquor made of the Yolk of an Egg, beaten with the Milk of a Figg Sprout, well ground together. This is a way of Painting, used by Antient Masters very much ; and it is a very lasting Way, there being yet things of Ghiotto’s doing upon Boards, that have lasted upwards of Two Hundred Years, and are still fresh and Beautiful. But since Oyl Painting came in, most have given over the way of Working in Distemper. Your Colours in this way are all Minerals, whereas in Working in Fresco, they must be all Earths.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

The Secret of Oyl Painting, consists in using Colours that are Ground with Oyl of Nut, or Linseed, and with these you paint upon a Cloth, which has first been primed with drying Colours, such as Cerus, Red Oaker, and Ombre, mingled together. This manner of painting, makes the Colours show more Lively than any other, and seems to give your Picture more Vivacity and Softness.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller,

The Secret of Oyl Painting, consists in using Colours that are Ground with Oyl of Nut, or Linseed, and with these you paint upon a Cloth, which has first been primed with drying Colours, such as Cerus, Red Oaker, and Ombre, mingled together. This manner of painting, makes the Colours show more Lively than any other, and seems to give your Picture more Vivacity and Softness.

Friend,

Can you Paint in Oyl upon a Wall ?

Traveller,

Yes, you may upon a dry Wall, having first Evened it ; and washed it over with Boyled Oyls, as long as it will drink any in, and when it is dry, prime it as you do a Cloth. There is another Way of doing it too, by applying a Paste or Plaister of a particular Composition, all over the Wall, then Washing it over with Linseed Oyl, then putting over that a Mixture of Pitch, Mastick, and Varnish, boyled together, and applyed with a great Brush, till it make a Couch, fit to receive your priming, and afterwards your Colours. Vassari gives the Receipt of a particular Composition, which he used in the Great Dukes Pallace at Florence, and which is very lasting.

Friend,

Pray what is painting in Chiaro Scuro ?

Traveller.

It is a manner of Painting that comes nearer Design than Colouring, it being first taken from the Imitation of the Statues of Marble, or of Bronze, or other Stones, and it is much used upon the Outside, and Fronts of Great Houses and Palaces, in Stories which seem to be of Marble, or Porphire, or any other Stone the Painter thinks fit to Imitate.

This Way of Painting, which seldom employs above two Colours, may be done in Fresco upon a Wall, which is the best Way ; or upon Cloth, and then it is most commonly employed for Designs of Triumphal Arches, and in Decorations of the Stage for Plays, and other such Entertainments Vassary, gives the secret of doing it either Way.

Friend,

I Am come to Summon you of your Promise [ndr : de lui raconter l’histoire de la peinture] ; and you may see by my Impatience ; that you have already made me a Lover of the Art.

Traveller,

I am glad to see it ; for it is no small Pleasure to think, that we are capable of procuring Pleasure to others, as I am sure I shall do to you, when I have made you thorowly capable of understanding the Beauty of an Art that has been the Admiration of Antiquity, and is still the greatest Charm of the most polite part of Mankind.

Friend,

Pray who do you mean by that glorious Epithete.

Traveller ;

I mean chiefly the Italians, to whom none can deny the Priviledge of having been the Civilisers of Europe, since Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Musick, Gardening, polite Conversation, and prudent Behaviour are, as I may call it, all of the Growth of their Countrey ; and I mean, besides all those in France, Spain, Germany, Low-Countreys, and England, who are Lovers of those Arts, and endeavour to promote them in their own Nation.

Friend,

I confess, they are all ravishing Entertainments, and infinitely to be preferr’d before our other sensual Delights, which destroy our Health, and dull our Minds ; and I hope they are travelling apace this way. But now pray satisfie my Curiosity about this Art of Painting, and let me know its whole History.

Timantes, on the contrary [ndr : Parrhasius vient d’être évoqué], was of a sweet, modest Temper, and was Admirable in the Expression of Passions ; as appear’d by his Famous Picture of the Sacrifice of Iphigenia ; where he drew so many different sorts of Sorrow upon the Faces of the Spectators, according to the Concerns they had in that Tragical Piece of Religion, that being at last come to Represent Agamemnon’s Face, who was Father to the Virgin, he found himself Exhausted, and not able to reach the Excess of Grief that naturally must have been showed in his Countenance upon that Occasion ; and therefore he covered his Face with a part of his Garment ; saving thereby the Honour of his Art , and yet giving some Idea of the greatness of the Father’s Sorrow. His particular Talent lay, in giving more to understand by his Pictures, than was really express’d in them.

Friend,

I observe, great Painters have generally, either Handsome Wives, or Beautiful Mistrisses, and they are for the most part, extreamly sensible to Beauty.

Travellour.

How can they be otherwise ? being such Judges as they are, of Feature and Proportion ; and having besides, so strong an Imagination, as they must have, to excell in their Art.

Traveller,

There remained in Græce some little footsteps of the Art [ndr : au Moyen Âge] ; and from thence it was, that about the Year 1250, there came some Painters, who could hardly be called Masters, having scarce any more knowledge of the Art than just to draw the Out-lines without either Grace or Proportion ; the first Schollar they made in Italy, was at Florence, and was called Cimabue ; who being helped by Nature, soon outdid his Masters, and began to give some strength to his Drawings, but still without any great Skill, as not understanding how to manage his Lights and Shadows, or indeed, how to Design truely ; it being it those days an unusual and unattempted thing to Draw after the Life.

Traveller.

There wanted a Spirit and Life, which their Successors gave to their Works [ndr : les successeurs désignent les artistes de la génération suivant celle de Mantegna, A. da Messina, etc.] ; [...] Traveller.

There wanted a Spirit and Life, which their Successors gave to their Works [ndr : les successeurs désignent les artistes de la génération suivant celle de Mantegna, A. da Messina, etc.] ; and particularly, an Easiness ; which hides the pains and labour that the Artist has been at ; it being with Painting as with Poetry ; where, the greatest Art, is to conceal Art ; that is, that the Spectator may think that easie, which cost the Painter infinite Toyl and Labour : They had not likewise, that sweet Union of their Colours which was afterwards found out, and first attempted by Francia Bolognese, and Pietro Perugino ; and so pleasing it was to the Eye, that the People came in flocks to stair upon their Works, thinking it impossible to do better ; but they were soon undeceived by Leonardo da Vinci ; whom we must own as the Father of the Third Age of Painting, which we call the Modern ; and in him nothing was wanting ; for besides strength of Design, and true Drawing, he gave better Rules, more exact Measures, and was more profound in the Art than any before him.

Traveller.

There wanted a Spirit and Life, which their Successors gave to their Works [ndr : les successeurs désignent les artistes de la génération suivant celle de Mantegna, A. da Messina, etc.] ; and particularly, an Easiness ; which hides the pains and labour that the Artist has been at ; it being with Painting as with Poetry ; where, the greatest Art, is to conceal Art ; that is, that the Spectator may think that easie, which cost the Painter infinite Toyl and Labour :

Giorgione was of the School of Venice, and the first that followed the Modern Tuscan way ; for having by chance seen some things of Leonardo da Vinci, with that new way of strong Shadows, it pleased him so much, that he followed it all his Life time, and imitated it prefectly in all his Oyl Paintings : he drew all after the Life, and had an excellent Colouring ; by which means he gave a Spirit to all he did ; which had not been seen in any Lombard Painter before him.

DA VINCI, Leonardo

École lombarde

GIORGIONE (Giorgio da Castelfranco)

Conceptual field(s)

DA VINCI, Leonardo

École lombarde

GIORGIONE (Giorgio da Castelfranco)

Conceptual field(s)

Raphael del Urbin was the greatest Painter that ever was ; having made himself a Manner out of the Study of the Antients and the Moderns, and taken the best out of both ; he was admirable for the easiness of Invention, Richness, and Order in his Composition, Nature herself was overcome by his Colouring, he was Judicious beyond measure, and proper to his Aptitudes ; in a word, he carried Painting in its greatest Perfection, and has been outdone by none : His particular Talent lay in Secret Graces, as Apelles’s did among the Ancients.

Perino del Vaga came to Rome in Raphael’s Time, and grew excellent by studying his and Michael Angelo’s Works ; he was a bold and strong Designer, having understood the Muscles in Naked Bodies as well as any of his time ; he had a particular Talent for Grottesk ; of which kind there are many Pieces of his in Rome ; but his chief Works are at Genova in the Pallace of Principe Doria ; he was a very universal Painter both in Fresco, Oyl and Distemper, and first taught the true working of Grottesks and Stucco Work.

Perino del Vaga came to Rome in Raphael’s Time, and grew excellent by studying his and Michael Angelo’s Works ; he was a bold and strong Designer, having understood the Muscles in Naked Bodies as well as any of his time ; he had a particular Talent for Grottesk ; of which kind there are many Pieces of his in Rome ; but his chief Works are at Genova in the Pallace of Principe Doria ; he was a very universal Painter both in Fresco, Oyl and Distemper, and first taught the true working of Grottesks and Stucco Work.

Michael Angelo Buonaroti was the greatest Designer that ever was, having studied Naked Bodies with great Care ; but he aiming always at showing the most difficult things of the Art, in the Contorsions of Members, and Convulsions of the Muscles, Contractions of the Nerves, &c. His Painting is not so agreeable, though much more profound and difficult than any other ; his Manner was Fierce, and almost Savage, having nothing of the Graces of Raphael, whose Naked Figures are dilicate and tender, and more like Flesh and Blood, whereas Michael Angelo doth not distinguish the Sexes nor the Ages so well, but makes all alike Musculous and Strong ; and who sees one Naked Figure of his doing, may reckon he has seen them all ; his Colouring is nothing near so Natural as Raphael’s, and in a word, for all Vasari commends him above the Skies, he was a better Sculptor than a Painter : One may of Raphael and of him, that their Characters were opposite, and both great Designers ; the one endeavouring to show the Difficulties of the Art, and the other aiming at Easiness ; in which, perhaps, there is as much Difficulty.

DEL VAGA, Perino (Pietro di Giovanni Bonaccorsi)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

VASARI, Giorgio

Conceptual field(s)

Michael Angelo Buonaroti was the greatest Designer that ever was, having studied Naked Bodies with great Care ; but he aiming always at showing the most difficult things of the Art, in the Contorsions of Members, and Convulsions of the Muscles, Contractions of the Nerves, &c. His Painting is not so agreeable, though much more profound and difficult than any other ; his Manner was Fierce, and almost Savage, having nothing of the Graces of Raphael, whose Naked Figures are dilicate and tender, and more like Flesh and Blood, whereas Michael Angelo doth not distinguish the Sexes nor the Ages so well, but makes all alike Musculous and Strong ;

Michael Angelo Buonaroti was the greatest Designer that ever was, having studied Naked Bodies with great Care ; but he aiming always at showing the most difficult things of the Art, in the Contorsions of Members, and Convulsions of the Muscles, Contractions of the Nerves, &c. His Painting is not so agreeable, though much more profound and difficult than any other ; his Manner was Fierce, and almost Savage, having nothing of the Graces of Raphael, whose Naked Figures are dilicate and tender, and more like Flesh and Blood, whereas Michael Angelo doth not distinguish the Sexes nor the Ages so well, but makes all alike Musculous and Strong ; and who sees one Naked Figure of his doing, may reckon he has seen them all ; his Colouring is nothing near so Natural as Raphael’s, and in a word, for all Vasari commends him above the Skies, he was a better Sculptor than a Painter : One may of Raphael and of him, that their Characters were opposite, and both great Designers ; the one endeavouring to show the Difficulties of the Art, and the other aiming at Easiness ; in which, perhaps, there is as much Difficulty.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller.

After the Death of Raphael and his Schollars (for, as for Michael Angelo he made no School) Painting seemed to be Decaying ; [...] But much about the same time, the Carraches of Bologna came to Rome, and the two Brothers Painted together the famous Gallery of the Pallazzo Farneze : Hannibal the Youngest, was much the greatest Master ; though his Eldest Brother Augustin was likewise admirable ; they renewed Raphael’s Manner ; and Hannibal particularly, had an admirable Genius to make proper to himself any Manner he saw, as he did by Correggio, both as to his Colouring, Tenderness, and Motions of the Figures ; in a word, he was a most Accomplish’d Painter, both for Design, Invention, Composition, Colouring, and all parts of Painting ; having a Soveraign Genius, which made him Master of a great School of the best Painters Italy has had.

Traveller.

After the Death of Raphael and his Schollars (for, as for Michael Angelo he made no School) Painting seemed to be Decaying ; and for some Years, there was hardly a Master of any Repute all over Italy. The two best at Rome were Joseph Arpino and Michael Angelo da Caravaggio, but both guilty of great Mistakes in their Art : the first followed purely his Fancy, or rather Humour, which was neither founded upon Nature nor Art, but had for Ground a certain Practical, Fantastical Idea which he had framed to himself. The other was a pure Naturalist, Copying Nature without distinction or discretion ; he understood little of Composition or Decorum, but was an admirable Colourer.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Titian was the best Colourer, perhaps, that ever was ; he Designed likewise very well, but not very exactly ; the Airs of his Heads for Women and Children are admirable, and his Drapery loose and noble ; his Portraits are all Master-pieces, no man having ever carried Face-Painting so far ; the Persons that he has drawn having all the Life and Spirit as if they were alive ;

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Titian was the best Colourer, perhaps, that ever was ; he Designed likewise very well, but not very exactly ; the Airs of his Heads for Women and Children are admirable, and his Drapery loose and noble ; his Portraits are all Master-pieces, no man having ever carried Face-Painting so far ; the Persons that he has drawn having all the Life and Spirit as if they were alive ; his Landskips are the Truest, best Coloured, and Strongest that ever were.

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller.

The World here in our Northern Climates has a Notion of Painters little nobler than of Joyners and Carpenters, or any other Mechanick, thinking that their Art is nothing but the daubing a few Colours upon a Cloth, and believing that nothing more ought to be expected from them at best, but the making a like Picture of any Bodys Face.

Which the most Ingenious amongst them perceiving, stop there ; and though their Genius would lead further into the noble part of History Painting, they check it, as useless to their Fortune, since they should have no Judges of their Abilities, nor any proportionable Reward of their Undertakings. So that till the Gentry of this Nation are better Judges of the Art, ’tis impossible we should ever have an Historical Painter of our own, nor that any excellent Forreigner should stay amongst us.

Conceptual field(s)

Expression Judges of the Art

Conceptual field(s)

Traveller.

I must then repeat to you what I told you at our first Meeting [ndr : Dialogue I, « Explaining the Art of Painting »] ; which is, That the Art of Painting has three Parts ; which are, Design, Colouring, and Invention ; and under this third, is that which we call Disposition ;

Traveller.

I must then repeat to you what I told you at our first Meeting [ndr : Dialogue I, « Explaining the Art of Painting »] ; which is, That the Art of Painting has three Parts ; which are, Design, Colouring, and Invention ; and under this third, is that which we call Disposition ; which is properly the Order in which all the Parts of the Story are disposed, so as to produce one effect according to the Design of the Painter ; and that is the first Effect which a good Piece of History is to produce in the Spectator ; that is, if it be a Picture of a joyful Event, that all that is in it be Gay and Smiling, to the very Landskips, Houses, Heavens, Cloaths, &c. And that all the Aptitudes tend to Mirth. The same, if the Story be Sad, or Solemn ; and so for the rest. And a Piece that does not do this at first sight, is most certainly faulty though it never so well Designed, or never so well Coloured ; nay, though there be Learning and Invention in it ; for as a Play that is designed to make me Laugh, is most certainly an ill one if it makes me Cry. So an Historical Piece that doth not produce the Effect it is designed for, cannot pretend to an Excellency, though it be never so finely Painted.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The next thing to be considered in an Historical Piece, is the Truth of the Drawings, and the Correction of the Design, as Painters call it ; that is, whether they have chosen to imitate Nature in her most Beautiful Part ; for though a Painter be the Copist of Nature, Yet he must not take her promiscuously, as he finds her, but have an Idea of all that is Fine and Beautiful in an Object, and choose to Represent that, as the Antients have done so admirably in their Paintings and Statues : And ’tis in this part that most of the Flemish Painters, even Rubens himself, have miscarryed, by making an ill Choice of Nature ; either because the Beautiful Natural is not the Product of their Countrey, or because they have not seen the Antique, which is the Correction of Nature by Art ; for we may truly say that the Antique is but the best of Nature ; and therefore all that resembles the Antique, will carry that Character along with it.

Friend,

I remember, you reckoned it to me among the Faults of some Painters, that they had studied too long upon the Statues of the Antients ; and that they had indeed thereby acquired the Correction of Design you speak of ; but they had by the same means lost that Vivacity and Life which is in Nature, and which is the true Grace of Painting.

École flamande

RUBENS, Peter Paul

Conceptual field(s)

The next thing to be considered in an Historical Piece, is the Truth of the Drawings, and the Correction of the Design, as Painters call it ; that is, whether they have chosen to imitate Nature in her most Beautiful Part ; for though a Painter be the Copist of Nature, Yet he must not take her promiscuously, as he finds her, but have an Idea of all that is Fine and Beautiful in an Object, and choose to Represent that, as the Antients have done so admirably in their Paintings and Statues : And ’tis in this part that most of the Flemish Painters, even Rubens himself, have miscarryed, by making an ill Choice of Nature ; either because the Beautiful Natural is not the Product of their Countrey, or because they have not seen the Antique, which is the Correction of Nature by Art ; for we may truly say that the Antique is but the best of Nature ; and therefore all that resembles the Antique, will carry that Character along with it.

Friend,

I remember, you reckoned it to me among the Faults of some Painters, that they had studied too long upon the Statues of the Antients ; and that they had indeed thereby acquired the Correction of Design you speak of ; but they had by the same means lost that Vivacity and Life which is in Nature, and which is the true Grace of Painting.

Traveller.

’Tis very true, that a Painter may fall into that Error, by giving himself up too much to the Antique ; therefore he must know, that his Profession is not tyed up to that exact Imitation of it as the Sculptor’s is, who must never depart from that exact Regularity of Proportion which the Antients have settled in their Statues ; but Painters Figures must be such as may seem rather to have been Models for the Antique, than drawn from it ; and a Painter that never has studied it at all, will never arrive at that as Raphael, and the best of the Lombard Painters have done ; who seem to have made no other Use of the Antique, than by that means to choose the most Beautiful of Nature.

École flamande

École lombarde

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RUBENS, Peter Paul

Conceptual field(s)

École flamande

École lombarde

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RUBENS, Peter Paul

Conceptual field(s)

École flamande

École lombarde

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RUBENS, Peter Paul

Conceptual field(s)

École flamande

École lombarde

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RUBENS, Peter Paul

Conceptual field(s)

École flamande

École lombarde

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

RUBENS, Peter Paul

Conceptual field(s)

The next thing to be considered in an Historical Piece, is the Truth of the Drawings, and the Correction of the Design, as Painters call it ; that is, whether they have chosen to imitate Nature in her most Beautiful Part ; for though a Painter be the Copist of Nature, Yet he must not take her promiscuously, as he finds her, but have an Idea of all that is Fine and Beautiful in an Object, and choose to Represent that, as the Antients have done so admirably in their Paintings and Statues : And ’tis in this part that most of the Flemish Painters, even Rubens himself, have miscarryed, by making an ill Choice of Nature ; either because the Beautiful Natural is not the Product of their Countrey, or because they have not seen the Antique, which is the Correction of Nature by Art ; for we may truly say that the Antique is but the best of Nature ; and therefore all that resembles the Antique, will carry that Character along with it.

École flamande

RUBENS, Peter Paul

Conceptual field(s)

Friend,

I remember, you reckoned it to me among the Faults of some Painters, that they had studied too long upon the Statues of the Antients ; and that they had indeed thereby acquired the Correction of Design you speak of ; but they had by the same means lost that Vivacity and Life which is in Nature, and which is the true Grace of Painting.

Traveller.

’Tis very true, that a Painter may fall into that Error, by giving himself up too much to the Antique ; therefore he must know, that his Profession is not tyed up to that exact Imitation of it as the Sculptor’s is, who must never depart from that exact Regularity of Proportion which the Antients have settled in their Statues ; but Painters Figures must be such as may seem rather to have been Models for the Antique, than drawn from it ; and a Painter that never has studied it at all, will never arrive at that as Raphael, and the best of the Lombard Painters have done ; who seem to have made no other Use of the Antique, than by that means to choose the most Beautiful of Nature.

École lombarde

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

Conceptual field(s)

There is another Caution to be observed too in this Choice of Forms, which is, to keep a Judicious Aptitude to the Story ; for if the Painter, for Example, is to draw Sampson, he must not give him the Softness and Tenderness he would give to Ganimedes ; nay, there is a difference to be made in the very same Figure at different times : and Hercules himself is to be made more Robust, fighting with Anteus, than when he sits in Dejanira’s Lap. But above all, the Painter must observe an equal Air, so as not to make one part Musculous and Strong, and the other Soft and Tender.

There is another Caution to be observed too in this Choice of Forms, which is, to keep a Judicious Aptitude to the Story ; for if the Painter, for Example, is to draw Sampson, he must not give him the Softness and Tenderness he would give to Ganimedes ; nay, there is a difference to be made in the very same Figure at different times : and Hercules himself is to be made more Robust, fighting with Anteus, than when he sits in Dejanira’s Lap. But above all, the Painter must observe an equal Air, so as not to make one part Musculous and Strong, and the other Soft and Tender.

There is another thing to be considered likewise upon the viewing of any Story ; which is, whether the Painter has used that Variety which Nature herself sets us a Pattern for, in not having made any one Face exactly like another, nor hardly any one Shape or Make of either Man or Woman. Therefore the Painter must also vary his Heads, his Bodies, his Aptitudes, and in a word, all the Members of the Humane Body, or else his Piece will Cloy, and Satiate the Eye.