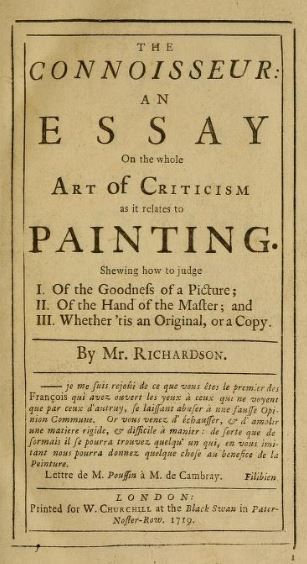

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, Two Discourses. I. An Essay on the whole Art of Criticism as it relates to Painting. Shewing how to judge I. Of the Goodness of a Picture ; II. Of the Hand of the Master ; and III. Whether ‘tis an Original, or a Copy. II. An Argument in behalf of the Science of a Connoisseur ; Wherein is shewn the Dignity, Certainty, Pleasure, and Advantage of it. Both by Mr. Richardson, London, W. Churchill, 1719.

Les Two Discourses sont composés de deux parties ou « discourses » – la pagination recommence dans le second. Le titre de ce dernier discours est variable : sur la page de garde de l’ouvrage, il s’agit de An Argument in behalf of the Science of a Connoisseur (n.p., p. 7 du pdf), tandis que sur la page de titre précédant ce discours, il s’agit de A Discourse on the Dignity, Certainty, Pleasure and Advantage, of the Science of a Connoisseur (p. 1 du second discours, p. 221 du pdf).

Les Two Discourses sont présentés par Richardson comme le premier ouvrage entièrement consacré à la manière de bien juger une peinture – L’idée du peintre parfait de Roger de Piles est évoqué dans l’introduction, mais selon Richardson ce travail n’est pas assez détaillé. Dans ses Two Discourses, Richardson donne ainsi davantage de renseignements sur la manière de reconnaître l’auteur d’un ouvrage, de distinguer une copie d’un original, etc. Il justifie sa démarche en précisant qu’à cause de sa profession et de son activité de collectionneur d’art, de nombreuses personnes lui demandent des conseils sur ces différents points. Il faut noter que le marché de l’art londonien connaissait un certain essor : de plus en plus d’individus achetaient alors des œuvres d’art, ces derniers désirant bien entendu acquérir des œuvres de bonne qualité, réalisées par tel ou tel grand maître. Richardson destine son texte à un public peu familier avec l’art et sa théorie – alors que son Essay on the Theory of Painting s’adressait à des peintres et un lectorat davantage connaisseur. Le but de l’auteur est donc d’aider des acquéreurs potentiels d’œuvres d’art, afin que les marchands n’exploitent pas leur ignorance en la matière pour leur vendre des peintures de mauvaise qualité à un prix trop élevé.

Richardson prend ainsi la plume dans un contexte nouveau. En outre, le Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne venait d’être créé : on cherchait alors à affirmer sa grandeur, y compris en peinture. Le premier texte écrit par Richardson, An Essay on the Theory of the Painting, allait déjà dans ce sens, puisque l’auteur tentait de promouvoir l’école anglaise de peinture, mais aussi de développer un discours britannique sur l’art, libéré des influences continentales. C’est ce qu’il poursuit dans ses Two Discourses, en tentant de développer un vocabulaire artistique anglais – quelques termes français et italiens, tels que tout-ensemble et mezzo-tinto, demeurent néanmoins présents. Richardson présente en outre une vision relativement nouvelle du Connoisseur et s’intéresse davantage à la réception des œuvres d’art plutôt qu’à leur production. Une particularité de ce texte réside dans la volonté de Richardson de promouvoir la Connaissance comme une branche de la connaissance humaine, comme une science à part entière, plutôt que comme une question d’opinion. Il développe de fait une vision très positive du Connoisseur, le présentant comme un individu cultivé, pouvant acquérir une certaine estime de la part de ses contemporains grâce à l’étude de la peinture quant à elle capable de transmettre des valeurs morales et sociales. Néanmoins, ce texte, contrairement aux deux autres écrits de Richardson, rencontra un succès moindre au XVIIIe siècle. Selon C. Gibson-Wood, cela s’explique notamment par la nouveauté du propos, mais aussi par la manière de s’exprimer de Richardson, qui réalise de nombreuses digressions sur la religion et la philosophie – toujours selon C. Gibson-Wood, l’ensemble de son propos est par ailleurs marqué par l’influence de John Locke (1632-1704) [1].

Une volonté d’indépendance de la part de Richardson se retrouve dans son absence de dédicace – c’était aussi le cas dans l’Essay on the Theory of Painting. Cette recherche se perçoit aussi dans la carrière de l’artiste puisqu’il refusa d’être nommé « Peintre du Roi » à deux reprises.

Ce texte ne comporte aucune illustration significative, seulement des bandeaux en début de chaque chapitre, ainsi que des lettrines. Néanmoins, plusieurs peintures sont citées, et notamment le portrait de la Comtesse Dowager of Exeter par Van Dyck (œuvre perdue, mais connue par une reproduction de W. Faithorne, gravure sur papier, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, P 2346-R) ou encore Tancrède et Herminie de Poussin (vers 1634, huile sur toile, 75.5 x 99.7 cm, Birmingham, University of Birmingham, The Barber Institute of Art, No.38.9), auxquelles Richardson consacre plusieurs pages.

Élodie Cayuela

[1] Gibson-Wood, 1982, p. 128-135 ; Gibson-Wood, 1984, p. 40-44 et Gibson-Wood, 2000, p. 181-182.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, A Discours on the Dignity, Certainty, Pleasure and Advantage, of the Science of a Connoisseur, London, W. Churchill, 1719.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, Two Discourses. I. An Essay on the Whole Art of Criticism as it relates to Painting. Shewing how to judge I. Of the Goodness of a Picture ; II. Of the Hand of the Master ; and III. Whether 'tis an Original, Or a Copy. II. An Argument in behalf of the Science of a Connoisseur ; Wherein is shewn the Dignity, Certainty, Pleasure, and Advantage of It. Both by Mr. Richardson, London, A. Bettesworth, 1725.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, The Works of Mr. Jonathan Richardson. Consisting of I. The Theory of Painting. II. Essay on the Art of Criticism, so far as it relates to Painting. III. The Science of a Connoisseur. All corrected and prepared for the Press By his Son Mr. J. Richardson, RICHARDSON, Jonathan Junior (éd.), London, T. Davies, 1773.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, The Works of Jonathan Richardson. Containing I. The Theory of Painting. II. Essay on the Art of Criticism, (So far as it relates to Painting). III. The Science of a Connoisseur. A New Edition, corrected, with the Additions of An Essay on the Knowledge of Prints, and Cautions to Collectors, Ornamented with Portraits by Worlidge, &c. of the most Eminent Painters mentioned. Dedicated, by Permission, to Sir Joshua Reynolds, London, T. et J. Egerton, 1792.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, The Works, Hildesheim, G. Olms, 1969.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, Two Discourses, Menston, Scolar Press, 1972.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan et RICHARDSON, Jonathan Junior, Traité de la peinture, et de la Sculpture. Par M. Richardson, Père & Fils. Divisé en trois tomes, Description de divers fameux tableaux, desseins, statues, bustes, bas-reliefs, &c., qui se trouvent en Italie ; Avec des remarques par Mrs Richardson, père & fils. Traduite de l'Anglois : Revue, Corrigée, & considérablement augmentée, dans cette traduction, par les auteurs. Où l'on a ajouté un discours préliminaire sur le beau idéal, des peintres, sculpteurs, & poëtes, par L. H. Ten Kate, trad. par RUTGERS, Antoine, Amsterdam, Herman Uytwerf, 1728, 2 vol., vol. II.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, Traité de la peinture et de la sculpture, trad. par RUTGERS, Antoine et TEN KATE, Lambert, Genève, Minkoff Reprint, 1972.

RICHARDSON, Jonathan, Traité de la peinture et de la sculpture, BAUDINO, Isabelle et OGÉE, Frédéric (éd.), Paris, École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2008.

SNELGROVE, Gordon William, The Work and Theories of Jonathan Richardson (1665-1745), Thesis, University of London, 1936.

PAKNADEL, Félix, Critique et peinture en Angleterre de 1660 à 1770, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Provence, 1978.

GIBSON-WOOD, Carol, « Jonathan Richardson and the Rationalization of Connoisseurship », Art History, 7/1, 1984, p. 38-56 [En ligne : http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1984.tb00127.x/abstract consulté le 23/06/2015].

GIBSON-WOOD, Carol, Studies in the Theory of Connoisseurship from Vasari to Morelli, New York, Garland, 1988.

HABERLAND, Irene, Jonathan Richardson, 1666-1745 : die Begründung der Kunstkennerschaft, Münster, LIT, 1991.

GIBSON-WOOD, Carol, Jonathan Richardson: Art Theorist of the English Enlightenment, New Haven - London, Yale University Press, 2000.

COWAN, Brian, « An Open Elite: the Peculiarities of Connoisseurship in Early Modern England », Modern Intellectual History, 1/2, 2004, p. 151-183.

GEEST, Simone von der, The Reasoning Eye: Jonathan Richardson's (1667-1745) Portrait Theory and Practice in the Context of the English Enlightenment, Thesis, University of London, 2005.

MOUNT, Harry, « The Monkey with the Magnifying Glass: Construction of the Connoisseur in Eighteenth-Century Britain », Oxford Art Journal, 29/2, 2006, p. 169-184 [En ligne : http://www.jstor.org/stable/3841010 consulté le 23/06/2015].

HAMLETT, Lydia, « Longinus and the Baroque Sublime in Britain », dans LLEWELLYN, Nigel et RIDING, Christine (éd.), The Art of the Sublime, 2013 [En ligne : https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/the-sublime/lydia-hamlett-longinus-and-the-baroque-sublime-in-britain-r1108498 consulté le 09/05/2016].

FILTERS

QUOTATIONS

Of the Goodness of a Picture, &c.

WHerefore callest thou me Good, there is none Good but One, that is God ? Said the Son of God to the young Man who prefac’d a Noble Question with that Complement. This is that Goodness that is Perfect, Simple, and Properly so call’d, ‘tis what is Peculiar to the Deity, and so to be found no where else. But there is another Improper, Imperfect, Comparative Goodness, and no other than this is to be had in the Works of Men, and this admits of various Degrees. This Distinction well consider’d, and apply’d to all the Occurrences of Life would contribute very much to the Improvement of our Happiness here ; it would teach us to Enjoy the Good before us, and not reject it upon account of the disagreeable Companion which is inseperable from it ; But the use I now would make of it is only to show that a Picture, Drawing, or Print may be Good tho’ it has several Faults ; To say otherwise is as absurd as to deny a thing is what ‘tis said to be, because it has properties which are Essential to it.

[…].

If in a Picture the Story be well chosen, and finely Told (at least) if not Improv’d, if it fill the Mind with Noble, and Instructive Ideas, I will not scruple to say ‘tis an excellent Picture, tho’ the Drawing be as Incorrect as that of Corregio, Titian, or Rubens ; the Colouring as Disagreeable as that of Polidore, Battista Franco, or Michael Angelo. Nay, tho’ there is no other Good but that of the Colouring, and the Pencil, I will dare to pronouce it a Good Picture ; that is, that ‘tis Good in those Respects. In the first Instance here is a fine Story artfully communicated to my Imagination, not by Speech, nor Writing, but in a manner preferable to either of them ; In the other there is a Beautiful, and Delightful Object, and a fine piece of Workmanship, to say no more of it.

There never was a Picture in the World without some Faults, And very rarely is there one to be found which is not notoriously Defective in some of the Parts of Painting. In judging of it’s Goodness as a Connoisseur, one should pronounce it such in proportion to the Number of the Good Qualities it has, and their Degrees of Goodness.

FRANCO, Battista

IL CORREGGIO (Antonio Allegri)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

POLIDORO DA CARAVAGGIO

RUBENS, Peter Paul

TIZIANO (Tiziano Vecellio)

Conceptual field(s)

If in a Picture the Story be well chosen, and finely Told (at least) if not Improv’d, if it fill the Mind with Noble, and Instructive Ideas, I will not scruple to say ‘tis an excellent Picture, tho’ the Drawing be as Incorrect as that of Corregio, Titian, or Rubens ; the Colouring as Disagreeable as that of Polidore, Battista Franco, or Michael Angelo. Nay, tho’ there is no other Good but that of the Colouring, and the Pencil, I will dare to pronouce it a Good Picture ; that is, that ‘tis Good in those Respects. In the first Instance here is a fine Story artfully communicated to my Imagination, not by Speech, nor Writing, but in a manner preferable to either of them ; In the other there is a Beautiful, and Delightful Object, and a fine piece of Workmanship, to say no more of it.

There never was a Picture in the World without some Faults, And very rarely is there one to be found which is not notoriously Defective in some of the Parts of Painting. In judging of it’s Goodness as a Connoisseur, one should pronounce it such in proportion to the Number of the Good Qualities it has, and their Degrees of Goodness.

FRANCO, Battista

IL CORREGGIO (Antonio Allegri)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

POLIDORO DA CARAVAGGIO

RUBENS, Peter Paul

TIZIANO (Tiziano Vecellio)

Conceptual field(s)

If in a Picture the Story be well chosen, and finely Told (at least) if not Improv’d, if it fill the Mind with Noble, and Instructive Ideas, I will not scruple to say ‘tis an excellent Picture, tho’ the Drawing be as Incorrect as that of Corregio, Titian, or Rubens ; the Colouring as Disagreeable as that of Polidore, Battista Franco, or Michael Angelo. Nay, tho’ there is no other Good but that of the Colouring, and the Pencil, I will dare to pronouce it a Good Picture ; that is, that ‘tis Good in those Respects

There never was a Picture in the World without some Faults, And very rarely is there one to be found which is not notoriously Defective in some of the Parts of Painting. In judging of it’s Goodness as a Connoisseur, one should pronounce it such in proportion to the Number of the Good Qualities it has, and their Degrees of Goodness.

There are certain Arguments, which a Connoisseur is utterly to reject, as not being such by which he is to form his Judgement, of what Use soever they may be to those who are incapable of judging otherwise, or who will not take the Pains to know better. [...] One of the commonest, and most deluding Arguments, that is used on this Occasion is, that ‘tis of the Hand of such a One. Tho’ this has no great Weight in it, even admitting it to be Really of that Hand, which very often ‘tis not : The best Masters have had their Beginnings, and Decays, and great Inequalities throughout their whole Lives, as shall be more fully noted hereafter. That ‘tis done by one who has had great Helps, and Opportunities of improving himself ; Or One that Says, he is a great Master, is what People are very ready to be cheated by, and not one Jot the less, for having found that they have been so cheated again, and again before, nay, tho’ they justly laugh at, and despise the Man at the same Time.

There are certain Arguments, which a Connoisseur is utterly to reject, as not being such by which he is to form his Judgement, of what Use soever they may be to those who are incapable of judging otherwise, or who will not take the Pains to know better. Some of these have really no Weight at all in them, the Best are very Precarious, and only serve to perswade us the Thing is good in general, not in what Respect it is so. That a Picture, or Drawing has been, or is much esteem’d by those who are believ’d to be good Judges ; Or is, or was Part of a famous Collection, cost so much, has a rich Frame, or the like. Whoever makes Use of such Arguments as these, besides that they are very fallacious, takes the Thing upon Trust, which a good Connoisseur should never condescend to do. That ‘tis Old, Italian, Rough, Smooth, &c. These are Circumstances hardly worth mentioning, and which belongs to Good, and Bad. A Picture, or Drawing may be too old to be good ; but in the Golden Age of Painting, which was that of Rafaelle, about Two Hundred Years ago, there were wretched Painters, as well as Before, and Since, and in Italy, as well as Elsewhere. Nor is a Picture the Better, or the Worse, for being Rough, or Smooth, simply consider’d.

There are certain Arguments, which a Connoisseur is utterly to reject, as not being such by which he is to form his Judgement, of what Use soever they may be to those who are incapable of judging otherwise, or who will not take the Pains to know better. Some of these have really no Weight at all in them, the Best are very Precarious, and only serve to perswade us the Thing is good in general, not in what Respect it is so. That a Picture, or Drawing has been, or is much esteem’d by those who are believ’d to be good Judges ; Or is, or was Part of a famous Collection, cost so much, has a rich Frame, or the like. Whoever makes Use of such Arguments as these, besides that they are very fallacious, takes the Thing upon Trust, which a good Connoisseur should never condescend to do. That ‘tis Old, Italian, Rough, Smooth, &c. These are Circumstances hardly worth mentioning, and which belongs to Good, and Bad. A Picture, or Drawing may be too old to be good ; but in the Golden Age of Painting, which was that of Rafaelle, about Two Hundred Years ago, there were wretched Painters, as well as Before, and Since, and in Italy, as well as Elsewhere. Nor is a Picture the Better, or the Worse, for being Rough, or Smooth, simply consider’d. One of the commonest, and most deluding Arguments, that is used on this Occasion is, that ‘tis of the Hand of such a One. Tho’ this has no great Weight in it, even admitting it to be Really of that Hand, which very often ‘tis not : The best Masters have had their Beginnings, and Decays, and great Inequalities throughout their whole Lives, as shall be more fully noted hereafter. That ‘tis done by one who has had great Helps, and Opportunities of improving himself ; Or One that Says, he is a great Master, is what People are very ready to be cheated by, and not one Jot the less, for having found that they have been so cheated again, and again before, nay, tho’ they justly laugh at, and despise the Man at the same Time. To infer a Thing Is, because it Ought to be, is unreasonable, because Experience shou’d teach us better ; but often we think there are Opportunities, and Advantages where there are none, or not in the Degree we imagine ; and to take a Man’s own Word, where his Interest, or Vanity shou’d make us suspect him is sufficiently unaccountable. Whoever builds upon a Supposition of the good Sense, and Integrity of Mankind has a very Sandy Foundation, and yet ‘tis what we find many a Popular Argument rests upon, in Other Cases, as well as in This. But, (as I said) whether These kind of Arguments above-mention’d have any thing in them, or not, a Connoisseur has nothing to do with them ; his Business is to judge from the Intrinsic Qualities of the thing itself ;

However I will here make him [ndr : au lecteur] an Offer of an Abstract of what I take to be those by which a Painter, or Connoisseur, may safely conduct himself, [...] II. The Expression must be Proper to the Subject, and the Characters of the Persons ; It must be strong, so that the Dumb-shew may be perfectly Well, and Readily understood. Every Part of the Picture must contribute to This End ; Colours, Animals, Draperies, and especially the Actions of the Figures, and above all the Airs of the Heads.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

However I will here make him [ndr : au lecteur] an Offer of an Abstract of what I take to be those by which a Painter, or Connoisseur, may safely conduct himself, referring to the Book it self for further Satisfaction. [...] VI. And Whether the Colours are laid on Thick, or Finely Wrought it must appear to be done by a Light, and Accurate Hand.

Conceptual field(s)

However I will here make him [ndr : au lecteur] an Offer of an Abstract of what I take to be those by which a Painter, or Connoisseur, may safely conduct himself, referring to the Book it self for further Satisfaction.

I. The Subject must be finely Imagin’d, and if possible Improv’d in the Painters Hands ; He must Think well as a Historian, Poet, Philosopher, or Divine, and moreover as a Painter in making a Wise Use of all the Advantages of his Art, and finding Expedients to supply its Defects.

All the different Degrees of Goodness in Painting may be reduc’d to these three General Classes. The Mediocre, or Indifferently Good, the Excellent, and the Sublime. The first is of a large Extent ; the second much Narrower ; and the Last still more so. I believe most people have a pretty Clear, and Just Idea of the two former ; the other is not so well understood ; which therefore I will define according to the Sense I have of it ;

All the different Degrees of Goodness in Painting may be reduc’d to these three General Classes. The Mediocre, or Indifferently Good, the Excellent, and the Sublime. The first is of a large Extent ; the second much Narrower ; and the Last still more so. I believe most people have a pretty Clear, and Just Idea of the two former ; the other is not so well understood ; which therefore I will define according to the Sense I have of it ; And I take it consist of some few of the Highest Degrees of Excellence in those Kinds, and Parts of Painting which are Excellent ; The Sublime therefore must be Marvellous, and Surprizing, It must strike vehemently upon the Mind, and Fill, and Captivate it Irresistably.

[…].

I confine the Sublime to History, and Portrait-Painting ; And These must excell in Grace, and Greatness, Invention, or Expression ; and that for Reasons which will be seen anon. Michael Angelo’s Great Style intitles Him to the Sublime, not his Drawing ; ‘tis that Greatness, and a competent degree of Grace, and not his Colouring that makes Titian capable of it : As Correggio’s Grace, with a sufficient mixture of Greatness gives this Noble Quality to His Works. Van Dyck’s Colouring, nor Pencil tho’ perfectly fine would never introduce him to the Sublime ; ‘tis his Expression, and that Grace, and Greatness he possess’d, (the Utmost that Portrait-Painting is Justly capable of) that sets some of his Works in that Exalted Class ; in which on That account he may perhaps take place of Rafaelle himself in That Kind of Painting, if that Great Man’s Fine, and Noble Idea’s carried him asmuch above Nature Then, as they did in History, where the utmost that can be done is commendable ; a due Subordination of Characters being preserved ; And thus (by the way) V. Dyck’s Colouring, and Pencil may be judg’d Equal to that of Corregio, or any other Master.

IL CORREGGIO (Antonio Allegri)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

TIZIANO (Tiziano Vecellio)

VAN DYCK, Antoon

Conceptual field(s)

I confine the Sublime to History, and Portrait-Painting ; And These must excell in Grace, and Greatness, Invention, or Expression ;

Conceptual field(s)

I confine the Sublime to History, and Portrait-Painting ; And These must excell in Grace, and Greatness, Invention, or Expression ; and that for Reasons which will be seen anon. Michael Angelo’s Great Style intitles Him to the Sublime, not his Drawing ; ‘tis that Greatness, and a competent degree of Grace, and not his Colouring that makes Titian capable of it : As Correggio’s Grace, with a sufficient mixture of Greatness gives this Noble Quality to His Works. Van Dyck’s Colouring, nor Pencil tho’ perfectly fine would never introduce him to the Sublime ; ‘tis his Expression, and that Grace, and Greatness he possess’d, (the Utmost that Portrait-Painting is Justly capable of) that sets some of his Works in that Exalted Class ;

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

I confine the Sublime to History, and Portrait-Painting ; And These must excell in Grace, and Greatness, Invention, or Expression ; and that for Reasons which will be seen anon. Michael Angelo’s Great Style intitles Him to the Sublime, not his Drawing ; ‘tis that Greatness, and a competent degree of Grace, and not his Colouring that makes Titian capable of it : As Correggio’s Grace, with a sufficient mixture of Greatness gives this Noble Quality to His Works. Van Dyck’s Colouring, nor Pencil tho’ perfectly fine would never introduce him to the Sublime ; ‘tis his Expression, and that Grace, and Greatness he possess’d, (the Utmost that Portrait-Painting is Justly capable of) that sets some of his Works in that Exalted Class ; in which on That account he may perhaps take place of Rafaelle himself in That Kind of Painting, if that Great Man’s Fine, and Noble Idea’s carried him asmuch above Nature Then, as they did in History, where the utmost that can be done is commendable ; a due Subordination of Characters being preserved ; And thus (by the way) V. Dyck’s Colouring, and Pencil may be judg’d Equal to that of Corregio, or any other Master.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

So in Painting the Sublimity of the Thought, or Expression may be consistent with bad Colouring, or Drawing, and these may help to produce that fine effect ; If they do not, That will make Them Overlook’d, or even Prejudice us in their favour ; However ‘tis not those Defects, but what is Excellent that is Sublime.

There is another kind of Goodness, and that is, As the Picture, or Drawing Answers the Ends intended to be serv’d by them ; Of which there are Several, but all reducible to these two General ones, Pleasure, and Improvement.

I am sorry the Great, and Principal End of the Art has hitherto been so little Consider’d ; I don’t mean by Gentlemen only, or by Low, Pretended Connoisseurs, But by those who ought to have gone higher, and to have Taught Others to have Followed them. ‘tis no Wonder if many who are accustom’d to Think Superficially look on Pictures as they would on a Piece of Rich Hangings ; Or if such as These, (and some Painters among the rest) fix upon the Pencil, the Colouring, or perhaps the Drawing, and some little Circumstantial Parts in the Picture, or even the just Representation of common Nature, without penetrating into the Idea of the Painter, and the Beauties of the History, or Fable. I say ‘tis no wonder if this so frequently happens when those whether Ancients or Moderns, who have wrote of Painting, in describing the Works of Painters in their Lives, or on other occasions have very rarely done any more ; Or in order to give us a Great Idea of some of the Best Painters have told us such Silly Stories as that of the Curtain of Parrhasius which deceiv’d Zeuxis, of the small lines one upon the other in the Contention between Apelles and Protogenes, (as I remember, ‘tis no matter of whom the Story goes) of the Circle of Giotto, and such like ; Trifles, which if a Man were never so expert at without going many degrees higher he would not be worthy the name of a Painter, much less of being remembred by Posterity with Honour.

‘tis true there are some Kinds of Pictures which can do no more than Please, as ‘tis the Case of some Kinds of Writings ; but one may as well say a Library is only for Ornament, and Ostentation as a Collection of Pictures, or Drawings. If That is the Only End, I am sure ‘tis not from any Defect in the Nature of the Things themselves.

I repeat it again, and would inculcate it, Painting is a fine piece of Workmanship ; ‘tis a Beautiful Ornament, and as such gives us Pleasure ; But over and above this We PAINTERS are upon the Level with Writers, as being Poets, Historians, Philosophers and Divines, we Entertain, and Instruct equally with Them. This is true and manifest beyond dispute whatever Mens Notions have been ;

To wake the Soul by tender Strokes of Art,

To raise the Genius, and to mend the Heart.

Mr. Pope.

is the business of Painting as well as of Tragedy.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

I am sorry the Great, and Principal End of the Art has hitherto been so little Consider’d ; I don’t mean by Gentlemen only, or by Low, Pretended Connoisseurs, But by those who ought to have gone higher, and to have Taught Others to have Followed them. ‘tis no Wonder if many who are accustom’d to Think Superficially look on Pictures as they would on a Piece of Rich Hangings ; Or if such as These, (and some Painters among the rest) fix upon the Pencil, the Colouring, or perhaps the Drawing, and some little Circumstantial Parts in the Picture, or even the just Representation of common Nature, without penetrating into the Idea of the Painter, and the Beauties of the History, or Fable.

‘tis true there are some Kinds of Pictures which can do no more than Please, as ‘tis the Case of some Kinds of Writings ; but one may as well say a Library is only for Ornament, and Ostentation as a Collection of Pictures, or Drawings. If That is the Only End, I am sure ‘tis not from any Defect in the Nature of the Things themselves.

I repeat it again, and would inculcate it, Painting is a fine piece of Workmanship ; ‘tis a Beautiful Ornament, and as such gives us Pleasure ; But over and above this We PAINTERS are upon the Level with Writers, as being Poets, Historians, Philosophers and Divines, we Entertain, and Instruct equally with Them.

‘tis true there are some Kinds of Pictures which can do no more than Please, as ‘tis the Case of some Kinds of Writings ; but one may as well say a Library is only for Ornament, and Ostentation as a Collection of Pictures, or Drawings. If That is the Only End, I am sure ‘tis not from any Defect in the Nature of the Things themselves.

When therefore we are to make a Judgment in what Degree of Goodness a Picture or Drawing is we should consider its Kind first, and then its several Parts. A History is preferrable to a Landscape, Sea-Piece, Animals, Fruit, Flowers, or any other Still-Life, pieces of Drollery, &c ; the reason is, the latter Kinds may Please, and in proportion as they do so they are Estimable, and that is according to every one’s Taste, but they cannot Improve the Mind, they excite no Noble Sentiments ; at least not as the other naturally does :

When therefore we are to make a Judgment in what Degree of Goodness a Picture or Drawing is we should consider its Kind first, and then its several Parts. A History is preferrable to a Landscape, Sea-Piece, Animals, Fruit, Flowers, or any other Still-Life, pieces of Drollery, &c ; the reason is, the latter Kinds may Please, and in proportion as they do so they are Estimable, and that is according to every one’s Taste, but they cannot Improve the Mind, they excite no Noble Sentiments ; at least not as the other naturally does : These not only give us Pleasure, as being Beautiful Objects, and Furnishing us with Ideas as the Other do, but the Pleasure we receive from Hence is Greater (I speak in General, and what the nature of the thing is capable of) ‘tis of a Nobler Kind than the Other ; and Then moreover the Mind may be Inrich’d, and made Better.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

A Portrait is a sort of General History of the Life of the Person it represents, not only to Him who is acquainted with it, but to Many Others, who upon Occasion of seeing it are frequently told, of what is most Material concerning Them, or their General Character at least ; The Face ; and Figure is also Describ’d and as much of the Character as appears by These, which oftentimes is here seen in a very great Degree. These therefore many times answer the Ends of Historical Pictures. And to Relations, or Friends give a Pleasure greater than any Other can.

There are many Single Heads which are Historical, and may be apply’d to several Stories. I have many such ; I have for Instance a Boy’s Head of Parmeggiano in whose Every Feature appears such an overflowing Joy, and that too not Common, but Holy, and Divine that I imagine him a little Angel rejoycing at the birth of the Son of God. I have another of Leonardo da Vinci of a Youth very Angelical, and in whom appears an Air such as Milton describes

[…]

This I suppose to be present at the Agony of our Lord, or his Crucifixion, or seeing him dead, with his Blessed Mother in that her vast Distress. Single Figures may be also thus apply’d, and made Historical. But Heads not Thus Applicable, must be reckoned in an Inferiour Class and more, or less so according as they happen to be.

Conceptual field(s)

A Portrait is a sort of General History of the Life of the Person it represents, not only to Him who is acquainted with it, but to Many Others, who upon Occasion of seeing it are frequently told, of what is most Material concerning Them, or their General Character at least ; The Face ; and Figure is also Describ’d and as much of the Character as appears by These, which oftentimes is here seen in a very great Degree. These therefore many times answer the Ends of Historical Pictures. And to Relations, or Friends give a Pleasure greater than any Other can. [...] As Portraits Unknown are not Equally considerable with Those that are ; Tho’ upon account of the Dignity of the Subject they may be reckon’d in the first Class of Those where in the Principal End of Painting is not full Answer’d ; but capable however of the Sublime.

The Kind of Picture, or Drawing having been consider’d, regard is to be had to the Parts of Painting ; we should see in which of These they excell, and in what Degree.

And these several Parts do not Equally contribute to the Ends of Painting : but (I think) ought to stand in this Order.

Grace and Greatness,

Invention,

Expression,

Composition,

Colouring,

Drawing,

Handling.

The Kind of Picture, or Drawing having been consider’d, regard is to be had to the Parts of Painting ; we should see in which of These they excell, and in what Degree.

And these several Parts do not Equally contribute to the Ends of Painting : but (I think) ought to stand in this Order.

Grace and Greatness,

Invention,

Expression,

Composition,

Colouring,

Drawing,

Handling.

The last can only Please ; The next (by which I understand Pure Nature, for the Great, and Gentile Style of Drawing falls into another Part) This also can only Please, Colouring Pleases more ; Composition Pleases at least as much as Colouring, and moreover helps to Instruct, as it makes those Parts that do so more conspicuous ; Expression Pleases, and Instructs Greatly ; the Invention does both in a higher Degree, and Grace, and Greatness above all. Nor is it peculiar to That Story, Fable, or whatever the Subject is, but in General raises our Idea of the Species, gives a most Delightful, Vertuous Pride, and kindles in Noble Minds an Ambition to act up to That Dignity Thus conceived to be in Humane Nature. In the Former Parts the Eye is employ’d, in the Other the Understanding.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

And thus too it is seen that Drawings (generally speaking) are Preferrable to Paintings, as having those Qualities which are most Excellent in a Higher Degree than Paintings generally have, or can possibly have, and the Others (excepting only Colouring) Equally with them. There is a Grace, a Delicacy, a Spirit in Drawings which when the Master attempts to give in Colours is commonly much diminish’d, both as being a sort of Coppying from those First Thoughts, and because the Nature of the Thing admits of no better.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Gentlemen may do as they please, the following Method [ndr : pour juger un tableau] seems to Me to be the most Natural, Convenient, and Proper.

Before you come so near the Picture to be Consider’d as to look into Particulars, or even to be able to know what the Subject of it is, at least before you take notice of That, Observe the Tout-ensemble of the Masses, and what Kind of one the Whole makes together.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Gentlemen may do as they please, the following Method [ndr : pour juger un tableau] seems to Me to be the most Natural, Convenient, and Proper.

Before you come so near the Picture to be Consider’d as to look into Particulars, or even to be able to know what the Subject of it is, at least before you take notice of That, Observe the Tout-ensemble of the Masses, and what Kind of one the Whole makes together. It will be proper at the same Distance to consider the General Colouring ; whether That be Grateful, Chearing, and Delightful to the Eye, or Disagreeable ;

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Gentlemen may do as they please, the following Method [ndr : pour juger un tableau] seems to Me to be the most Natural, Convenient, and Proper.

Before you come so near the Picture to be Consider’d as to look into Particulars, or even to be able to know what the Subject of it is, at least before you take notice of That, Observe the Tout-ensemble of the Masses, and what Kind of one the Whole makes together. It will be proper at the same Distance to consider the General Colouring ; whether That be Grateful, Chearing, and Delightful to the Eye, or Disagreeable ; Then let the Composition be Examin’d Near, and see the Contrasts, and other Particularities relating to it, and so finish your Observations on That Head.

Gentlemen may do as they please, the following Method [ndr : pour juger un tableau] seems to Me to be the most Natural, Convenient, and Proper.

Before you come so near the Picture to be Consider’d as to look into Particulars, or even to be able to know what the Subject of it is, at least before you take notice of That, Observe the Tout-ensemble of the Masses, and what Kind of one the Whole makes together. It will be proper at the same Distance to consider the General Colouring ; whether That be Grateful, Chearing, and Delightful to the Eye, or Disagreeable ; Then let the Composition be Examin’d Near, and see the Contrasts, and other Particularities relating to it, and so finish your Observations on That Head. The same Then may be done with respect to the Colouring ;

Gentlemen may do as they please, the following Method [ndr : pour juger un tableau] seems to Me to be the most Natural, Convenient, and Proper.

Before you come so near the Picture to be Consider’d as to look into Particulars, or even to be able to know what the Subject of it is, at least before you take notice of That, Observe the Tout-ensemble of the Masses, and what Kind of one the Whole makes together. It will be proper at the same Distance to consider the General Colouring ; whether That be Grateful, Chearing, and Delightful to the Eye, or Disagreeable ; Then let the Composition be Examin’d Near, and see the Contrasts, and other Particularities relating to it, and so finish your Observations on That Head. The same Then may be done with respect to the Colouring ; then the Handling, and afterwards the Drawing ; These being dispatch’d the Mind is at liberty carefully consider the Invention ; then to see how well the Expression is perform’d, And Lastly, What Grace and Greatness is spread throughout, and how suitable to each Character.

Association intéressante entre Natural, Convenient et Proper

Conceptual field(s)

Association intéressante entre Natural, Convenient et Proper

Conceptual field(s)

Association intéressante entre Natural, Convenient et Proper

Conceptual field(s)

Notion rattachée à Grace et Greatness

Conceptual field(s)

Monsieur de Piles has a pretty Invention of a Scale whereby he gives an Idea in short of the Merit of the Painters, I have given some Account of it in the latter end of my former Essay : This, with a little Alteration and Improvement may be of great use to Lovers of Art, and Connoisseurs.

Conceptual field(s)

I will give a Specimen of what I have been proposing [ndr : dans sa manière de juger une peinture], and the Subject shall be a Portrait of V. Dyck which I have, ‘tis a Half-length of a Countess Dowager of Exeter, as I learn from the Print made of it by Faithorn, and that is almost all one can learn from That concerning the Picture besides the General Attitude, and Disposition of it.

The Dress is Black Velvet, and That appearing almost one large Spot, the Lights not being so managed as to connect it, with the other parts of the Picture ;

I will give a Specimen of what I have been proposing [ndr : dans sa manière de juger une peinture], and the Subject shall be a Portrait of V. Dyck which I have, ‘tis a Half-length of a Countess Dowager of Exeter, as I learn from the Print made of it by Faithorn, and that is almost all one can learn from That concerning the Picture besides the General Attitude, and Disposition of it. [...] But so far as the Head, and almost to the Wast, with the Curtain behind, there is an Admirable Harmony, the Chair also makes a Medium between the Figure, and the Ground. The Eye is deliver’d down into that Dead Black Spot the Drapery with great Ease, the Neck is cover’d with Linnen, and at the Breast the top of the Stomacher makes a streight line. This would have been very harsh, and disagreeable but that ‘tis very Artfully broken by the Bowes of a Knot of narrow Ribbon which rise above that Line in fine, well-contrasted Shapes. This Knot fastens a Jewel on the Breast, which also helps to produce the Harmony of this part of the Picture, and the white Gloves which the Lady holds in her Left Hand, helps the Composition something as they vary That Light Spot from That which the Other Hand, and Linnen makes.

Conceptual field(s)

I will give a Specimen of what I have been proposing [ndr : dans sa manière de juger une peinture], and the Subject shall be a Portrait of V. Dyck which I have, ‘tis a Half-length of a Countess Dowager of Exeter, as I learn from the Print made of it by Faithorn, and that is almost all one can learn from That concerning the Picture besides the General Attitude, and Disposition of it.

The Dress is Black Velvet, and That appearing almost one large Spot, the Lights not being so managed as to connect it, with the other parts of the Picture ; The Face, and Linnen at the Neck, and the two Hands, and broad Cuffs at the Wrists being by this means three several Spots of Light, and that near of an equal degree ; and forming almost an Equilateral Triangle, the Base of which is parallel to that of the Picture, the Composition is Defective ; and this occasion’d chiefly from the want of those Lights upon the Black.

I will give a Specimen of what I have been proposing [ndr : dans sa manière de juger une peinture], and the Subject shall be a Portrait of V. Dyck which I have, ‘tis a Half-length of a Countess Dowager of Exeter, as I learn from the Print made of it by Faithorn, and that is almost all one can learn from That concerning the Picture besides the General Attitude, and Disposition of it.

The Dress is Black Velvet, and That appearing almost one large Spot, the Lights not being so managed as to connect it, with the other parts of the Picture ; The Face, and Linnen at the Neck, and the two Hands, and broad Cuffs at the Wrists being by this means three several Spots of Light, and that near of an equal degree ; and forming almost an Equilateral Triangle, the Base of which is parallel to that of the Picture, the Composition is Defective ; and this occasion’d chiefly from the want of those Lights upon the Black. But so far as the Head, and almost to the Wast, with the Curtain behind, there is an Admirable Harmony, the Chair also makes a Medium between the Figure, and the Ground. The Eye is deliver’d down into that Dead Black Spot the Drapery with great Ease, the Neck is cover’d with Linnen, and at the Breast the top of the Stomacher makes a streight line. This would have been very harsh, and disagreeable but that ‘tis very Artfully broken by the Bowes of a Knot of narrow Ribbon which rise above that Line in fine, well-contrasted Shapes. This Knot fastens a Jewel on the Breast, which also helps to produce the Harmony of this part of the Picture, and the white Gloves which the Lady holds in her Left Hand, helps the Composition something as they vary That Light Spot from That which the Other Hand, and Linnen makes.

Conceptual field(s)

The Tout-ensemble of the Colouring [ndr : dans le portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck] is Extreamly Beautiful ; ‘tis Solemn, but Warm, Mellow, Clean, and Natural ; the Flesh, which is exquisitely good, especially the Face, the Black Habit, the Linnen and Cushion, the Chair of the Crimson Velvet, and the Gold Flower’d Curtain mixt with a little Crimson have an Admirable effect, and would be Perfect were there a Middle Tinct amongst the Black.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The Face, and Hands, are a Model for a Pencil in Portrait-Painting [ndr : il s’agit du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck] ; ‘tis not V. Dyck’s first Labour’d Flemish Manner, nor in the least Careless, or Slight ;

The Face, and Hands, are a Model for a Pencil in Portrait-Painting [ndr : il s’agit du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck] ; ‘tis not V. Dyck’s first Labour’d Flemish Manner, nor in the least Careless, or Slight ; the Colours are well wrought, and Touch’d in his best Style ;

The Face, and Hands, are a Model for a Pencil in Portrait-Painting [ndr : il s’agit du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck] ; ‘tis not V. Dyck’s first Labour’d Flemish Manner, nor in the least Careless, or Slight ; the Colours are well wrought, and Touch’d in his best Style ; that is, the Best that ever Man had for Portraits ; nor is the Curtain in the least inferiour in this Particular, tho’ the Manner is vary’d as it ought to be, the Pencil is There more seen than in the Flesh ; the Hair, Veil, Chair, and indeed throughout except the Black Gown is finely Handled.

The Face is admirably well Drawn [ndr : du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck]; the Features are pronounc’d Clean, and Firmly, so as ‘tis evident he that did That conceiv’d strong, and Distinct Ideas, and saw wherein the Lines that form’d Those differ’d from all others ;

The Face is admirably well Drawn [ndr : du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck]; the Features are pronounc’d Clean, and Firmly, so as ‘tis evident he that did That conceiv’d strong, and Distinct Ideas, and saw wherein the Lines that form’d Those differ’d from all others ; there appears nothing of the Antique, or Raffaelle-Tast of Designing, but Nature, well understood, well chosen, and well manag’d ;

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The Face is admirably well Drawn [ndr : du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck]; the Features are pronounc’d Clean, and Firmly, so as ‘tis evident he that did That conceiv’d strong, and Distinct Ideas, and saw wherein the Lines that form’d Those differ’d from all others ; there appears nothing of the Antique, or Raffaelle-Tast of Designing, but Nature, well understood, well chosen, and well manag’d ; the Lights, and Shadows are justly plac’d, and shap’d, and both sides of the Face answer well to each other.

The Face is admirably well Drawn [ndr : du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck]; the Features are pronounc’d Clean, and Firmly, so as ‘tis evident he that did That conceiv’d strong, and Distinct Ideas, and saw wherein the Lines that form’d Those differ’d from all others ; there appears nothing of the Antique, or Raffaelle-Tast of Designing, but Nature, well understood, well chosen, and well manag’d ; the Lights, and Shadows are justly plac’d, and shap’d, and both sides of the Face answer well to each other.

The Face is admirably well Drawn [ndr : du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck]; the Features are pronounc’d Clean, and Firmly, so as ‘tis evident he that did That conceiv’d strong, and Distinct Ideas, and saw wherein the Lines that form’d Those differ’d from all others ; there appears nothing of the Antique, or Raffaelle-Tast of Designing, but Nature, well understood, well chosen, and well manag’d ; the Lights, and Shadows are justly plac’d, and shap’d, and both sides of the Face answer well to each other. The Jewel on the Breast is finely dispos’d, and directs the Eye to the line between the Breasts, and gives the Body there a great Relief, the Girdle also has a good effect, for by being mark’d pretty strongly the Eye is shown the Wast very readily. The Linnen, the Jewel, the Gold Curtain, the Gause Veil are all extreamly Natural, that is they are justly Drawn, and Colour’d.

Conceptual field(s)

These being thus dispatch’d we are at liberty to consider the Invention [ndr : il s’agit du portrait de la comtesse Dowager of Exeter, par Van Dyck]. V. Dyck’s Thought seems to have been that the Lady should be sitting in her Own Room receiving a Visit of Condolance from an Inferiour with great Benignity ; as shall be seen presently, I would here observe the Beauty, and Propriety of this Thought. For by This the Picture is not an Insipid Representation of a Face, and Dress, but here is also a Picture of the Mind, and what more proper to a Widow than Sorrow ? And more becoming a Person of Quality than Humility, and Benevolence ?

Conceptual field(s)

Never was a Calm Becoming Sorrow better Express’d than in this Face [ndr : il s’agit du portrait de la Comtesse Dowager d’Exeter, par Van Dyck] chiefly there where ‘tis always most conspicuous that is in the Eyes : Not Guido Reni, no, nor Raffaelle himself could have Conceiv’d a Passion with more Delicacy, or more Strongly Express’d it ! To which also the Whole Attitude of the Figure contributes not a little, her Right Hand drops easily from the Elbow of the Chair which her Wrist lightly rests upon, the other lies in her Lap towards her Left Knees, all which together appears so Easy, and Careless, that what is Lost in the Composition by the Regularity I have taken notice of, is Gain’d in the Expression ; which being of greater Consequence justifies V. Dyck in the main, and shows his great Judgment, for tho’ as it Is, there is (as I said) something amiss, I cannot conceive any way of Avoiding That Inconvenience without a Greater.

And notwithstanding the Defects I have taken the Liberty to remark with the same Indifferency as I have observed the Beauties, that is, without the least regard to the Great Name of the Master, There is a Grace throughout that Charms, and a Greatness that Commands Respect [ndr : dans le portrait de la comtesse Dowager d’Exeter, par Van Dyck]; She appears at first Sight to be a Well-bred Woman of Quality ; ‘tis in her Face, and in her Mien ; and as her Dress, Ornaments, and Furniture contribute something to the Greatness, the Gause Veil coming over her Forehead, and the Hem of it hiding a Defect (which was want of Eye-brows,) is a fine Artifice to give more Grace. This Grace, and Greatness is not that of Raffaelle, or the Antique but ‘tis what is suitable to a Portrait ; and one of Her Age, and Character, and consequently better than if she had appear’d with the Grace of a Venus, or Helena, or the Majesty of a Minerva, or Semiramis.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The Beauty, and Harmony of the Colouring gives Me a great Degree of Pleasure [ndr : dans le portrait de la comtesse Dowager d’Exeter par Van Dyck] ; for tho’ This is Grave and Solid, it has a Beauty not less than what is Bright, and Gay. So much of the Composition as is Good does also much Delight the Eye ; And tho’ the Lady is not Young, nor remarkably Handsome, the Grace, and Greatness that is here represented pleases exceedingly. In a Word, as throughout this whole Picture one sees Instances of an Accurate Hand, and Fine Thought, These must give proportionable Pleasure to so hearty a Lover as I am.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The Goût is a mixture of Poussin’s usual Manner [ndr : il s’agit ici du Tancrède et Herminie, réalisé par Poussin], and (what is very rare) a great deal of Guilio, particulary in the Head, and Attitude of the Lady, and both the Horses ; Tancred is naked to the Wast having been stripp’d by Erminia and his ’Squire to search for his Wounds, he has a piece of loose Drapery which is Yellow, bearing upon the Red in the Middle Tincts, and Shadows, this is thrown over his Belly, and Thighs, and lyes a good length upon the ground ; ’twas doubtless painted by the Life, and is intirely of a Modern Taste. And that nothing might be shocking, or disagreeable, the wounds are much hid, nor is his Body, or Garment stain’d with Blood, only some appears here, and there upon the ground just below the Drapery, as if it flow’d from some Wounds which That cover’d ;

The Habits are not those of the Age in which the Scene of the Fable is laid, These must have been Gothick, and Disagreeable, it being at the latter end of the 11th, or the beginning of the 12th Century [ndr : il s’agit ici du Tancrède et Herminie, réalisé par Poussin]. Erminia is clad in Blue, admirably folded, and in a great Style, something like that of Giulio, but more upon the Antique, or, Raffaelle ;

The Habits are not those of the Age in which the Scene of the Fable is laid, These must have been Gothick, and Disagreeable, it being at the latter end of the 11th, or the beginning of the 12th Century [ndr : il s’agit ici du Tancrède et Herminie, réalisé par Poussin]. Erminia is clad in Blue, admirably folded, and in a great Style, something like that of Giulio, but more upon the Antique, or, Raffaelle ; one of her feet is seen which is very Gentile, and Artfully dispos’d ; [...] The two Cupidons are admirably well dispos’d, and enrich, and enliven the Picture ; as does the Helmet, Shield, and Armour of Tancred which lyes at his Feet. The Attitudes of the Horses are exceeding fine, One of them turns his head backwards with great Spirit, the other has his Hinder part rais’d, which not only has a Noble effect in the Picture, but helps to tell what kind of place it was, which was rough, and unfrequented.

The Habits are not those of the Age in which the Scene of the Fable is laid, These must have been Gothick, and Disagreeable, it being at the latter end of the 11th, or the beginning of the 12th Century [ndr : il s’agit ici du Tancrède et Herminie, réalisé par Poussin]. Erminia is clad in Blue, admirably folded, and in a great Style, something like that of Giulio, but more upon the Antique, or, Raffaelle ; one of her feet is seen which is very Gentile, and Artfully dispos’d ; her Sandal is very particular, for ‘tis a little rais’d under the Heel as our Children’s Shoes. Vafrino has a Helmet on with a large, bent Plate of Gold instead, and something with the turn of a Feather. We don’t remember any thing like it in the Antique ; There is no such thing in the Column of Trajan, nor that of Antonine (as ‘tis usually call’d tho’ ‘tis now known to be of M. Aurelius) nor (I believe) in the Works of Raffaelle, Guilio, or Polydore when they have imitated the Ancients, tho’ These, especially the two former have taken like Liberties, and departing from the Simplicity of their Great Masters have in these Instances given a little into the Gothick tast : This is probably Poussin’s own Invention, and has such an effect that I cannot imagine any thing else could possibly have been so well. The Figure is in Armour, not with Labells, but Scarlet Drapery where those usually are which also is Antique.

The Habits are not those of the Age in which the Scene of the Fable is laid, These must have been Gothick, and Disagreeable, it being at the latter end of the 11th, or the beginning of the 12th Century [ndr : il s’agit ici du Tancrède et Herminie, réalisé par Poussin]. Erminia is clad in Blue, admirably folded, and in a great Style, something like that of Giulio, but more upon the Antique, or, Raffaelle ; one of her feet is seen which is very Gentile, and Artfully dispos’d ; her Sandal is very particular, for ‘tis a little rais’d under the Heel as our Children’s Shoes. Vafrino has a Helmet on with a large, bent Plate of Gold instead, and something with the turn of a Feather. We don’t remember any thing like it in the Antique ; There is no such thing in the Column of Trajan, nor that of Antonine (as ‘tis usually call’d tho’ ‘tis now known to be of M. Aurelius) nor (I believe) in the Works of Raffaelle, Guilio, or Polydore when they have imitated the Ancients, tho’ These, especially the two former have taken like Liberties, and departing from the Simplicity of their Great Masters have in these Instances given a little into the Gothick tast : This is probably Poussin’s own Invention, and has such an effect that I cannot imagine any thing else could possibly have been so well. The Figure is in Armour, not with Labells, but Scarlet Drapery where those usually are which also is Antique. The two Cupidons are admirably well dispos’d, and enrich, and enliven the Picture ; as does the Helmet, Shield, and Armour of Tancred which lyes at his Feet. The Attitudes of the Horses are exceeding fine, One of them turns his head backwards with great Spirit, the other has his Hinder part rais’d, which not only has a Noble effect in the Picture, but helps to tell what kind of place it was, which was rough, and unfrequented.

‘Tis observable that tho’ Tasso says only Erminia cuts off her hair, Poussin was forc’d to explain what she cut it off withal, and he has given her her Lover’s Sword [ndr : Poussin, Herminie et Tancrède]. We don’t at all question but there will be those who will fancy they have here discover’d a notorious Absurdity in Poussin, it being impossible to cut Hair with a Sword ; but though it be, a Pair of Scissars instead of it, though much the sitter for the purpose, had spoil’d the Picture ; Painting, and Poetry equally disdain such low, and common things. This is a Lycence much of the same kind with that of Raffael in the Carton of the Draught of Fishes, where the Boat is by much too little for the Figures that are in it ; or with the Laacon, who is naked, whereas being a Priest in his Sacerdotal Office, he must have been suppos’d to have been clad : But we need not tell you, Sir [ndr : ce passage est la retranscription d’une lettre de Richardson, père et fils, à un « gentleman at Rotterdam »], why those Noble pieces of Painting, and Sculpture were so managed.

AGESANDROS OF RHODES, ATHENODOROS et POLYDOROS, Laocoon et ses fils, 40 avant J.C. - 20 avant J.C., marbre, 208 x 163 x 112, Vatican, Vatican, Museo Pio-Clementino, Inv. 1059.

POUSSIN, Nicolas, Tancrède et Herminie, v. 1634, huile sur toile, 75,5 X 99,7 , Birmingham, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, No.38.9.

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio) , La pêche miraculeuse, 1515 - 1516, gouache et huile sur carton, 320 x 390, London, Victoria & Albert Museum, ROYAL LOANS.2.

Conceptual field(s)

The Composition is unexceptionable [ndr : dans Poussin, Tancrède et Herminie] : There are innumerable Instances of Beautiful Contrasts ; [...] The Picture is highly finish’d, even in the parts the most inconsiderable, but in once, or two places there is a little heaviness of Hand ; The Drawing is firmly pronounc’d, and Sometimes, chiefly in the Faces, Hands and Feet ‘tis mark’d more than ordinary with the point of the Pencil.

The Composition is unexceptionable [ndr : dans Poussin, Tancrède et Herminie] : There are innumerable Instances of Beautiful Contrasts ; Of this kind are the several Characters of the Persons, (all which are Excellent in their several kinds) and the several Habits : Tancred is half Naked : Erminia’s Sex distinguishes Her from all the rest ; as Vafrino’s Armour, and Helmet shews Him to be Inferiour to Tancred, (His lying by him) and Argante’s Armour differs from both of them. The various positions of the Limbs in all the Figures are also finely Contrasted, and altogether have a lovely effect ; Nor did I ever see a greater Harmony, nor more Art to produce it in any Picture of what Master soever, whether as to the Easy Gradation from the Principal, to the Subordinate Parts, the Connection of one with another, by the degrees of the Lights, and Shadows, and the Tincts of the Colours.

And These too are Good throughout ; They are not Glaring, as the Subject, and the Time of the Story (which was after Sun-set) requires : Nor is the Colouring like that of Titian, Corregio, Rubens, or those fine Colourists, But ‘tis Warm, and Mellow, ‘tis Agreeable, and of a Taste which none but a Great Man could fall into : And without considering it as a Story, or the Imitation of any thing in Nature the Tout-ensemble of the Colours is a Beautiful, and Delightful Object.

You know (Sir) [ndr : ce passage est la retranscription d’une lettre de Richardson, père et fils, à un « gentleman at Rotterdam] the Drawing of Poussin who have several Admirable Pictures of his hand, This we believe is not Inferiour to any to be seen of him. But there is an Oversight, or two in the Perspective ; the Sword Erminia holds appears by the Pommel of it to incline with the point going off, but by the Blade it seems to be upright ; the other is not worth mentioning.

The Picture is highly finish’d, even in the parts the most inconsiderable, but in once, or two places there is a little heaviness of Hand ; The Drawing is firmly pronounc’d, and Sometimes, chiefly in the Faces, Hands and Feet ‘tis mark’d more than ordinary with the point of the Pencil.

The Composition is unexceptionable [ndr : dans Poussin, Tancrède et Herminie] : There are innumerable Instances of Beautiful Contrasts ; Of this kind are the several Characters of the Persons, (all which are Excellent in their several kinds) and the several Habits : Tancred is half Naked : Erminia’s Sex distinguishes Her from all the rest ; as Vafrino’s Armour, and Helmet shews Him to be Inferiour to Tancred, (His lying by him) and Argante’s Armour differs from both of them. The various positions of the Limbs in all the Figures are also finely Contrasted, and altogether have a lovely effect ; Nor did I ever see a greater Harmony, nor more Art to produce it in any Picture of what Master soever, whether as to the Easy Gradation from the Principal, to the Subordinate Parts, the Connection of one with another, by the degrees of the Lights, and Shadows, and the Tincts of the Colours.

And These too are Good throughout ; They are not Glaring, as the Subject, and the Time of the Story (which was after Sun-set) requires : Nor is the Colouring like that of Titian, Corregio, Rubens, or those fine Colourists, But ‘tis Warm, and Mellow, ‘tis Agreeable, and of a Taste which none but a Great Man could fall into : And without considering it as a Story, or the Imitation of any thing in Nature the Tout-ensemble of the Colours is a Beautiful, and Delightful Object.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

The Composition is unexceptionable [ndr : dans Poussin, Tancrède et Herminie] : There are innumerable Instances of Beautiful Contrasts ; Of this kind are the several Characters of the Persons, (all which are Excellent in their several kinds) and the several Habits : Tancred is half Naked : Erminia’s Sex distinguishes Her from all the rest ; as Vafrino’s Armour, and Helmet shews Him to be Inferiour to Tancred, (His lying by him) and Argante’s Armour differs from both of them. The various positions of the Limbs in all the Figures are also finely Contrasted, and altogether have a lovely effect ; Nor did I ever see a greater Harmony, nor more Art to produce it in any Picture of what Master soever, whether as to the Easy Gradation from the Principal, to the Subordinate Parts, the Connection of one with another, by the degrees of the Lights, and Shadows, and the Tincts of the Colours.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

We will only observe further the different Idea given by the Painter, and the Poet [ndr : dans Poussin, Tancrède et Herminie et le Tasse, dans le passage de la Jérusalem céleste s’y rapportant]. A Reader of Tasso that thought less finely than Poussin would form in his Imagination a Picture, but not Such a one as This. He would see a Man of a less Lovely, and Beautiful Aspect, Pale, and all cut, and mangled, his Body, and Garments smear’d with Blood : He would see Erminia, not such a one as Poussin has made her ; and a thousand to one with a pair of Scissars in her hand, but certainly not with Tancred’s Sword : The two Amoretto’s would never enter into his Mind : Horses he would see, and let ‘em be the finest he had ever seen they would be less fine than These, and so of the rest. The Painter has made a finer Story than the Poet, tho’ his Readers were Equal to himself, but without all Comparison much finer than it can appear to the Generality of them. And he has moreover not only known how to make use of the Advantages This Art has over that of his Competitor, but in what it is Defective in the Comparison he has supply’d it with such Address that one cannot but rejoyce in the Defect which occasion’d such a Beautiful Expedient.

Every thing that is done is in pursuance of some Ideas the Master has, whether he can reach with his Hand, what his Mind has conceiv’d, or no ; and this is true in every Part of Painting. As for Invention, Expression, Disposition, and Grace, and Greatness. These every body must see direct us plainly to the Manner of Thinking, to the Idea the Painter had ; but even in Drawing, Colouring, and Handling, in These also are seen his Manner of Thinking upon those Subjects, One may by These guess at his Ideas of what is in Nature, or what was to be wish’d for, or Chosen at least. Nevertheless when the Idea, or Manner of Thinking in a Picture or Drawing is opposed to the Executive part, ‘tis commonly understood of these four first mention’d, As the other 3 are imply’d by its opposite.

Conceptual field(s)

The several Manners of the Painters consequently are to be known, whether in Pictures, or Drawings ; as also those of the Gravers in Copper, or Wood, Etchers, or others by whom Prints are made, if we have a sufficient quantity of their Works to form our Judgments upon.

There are such Peculiarities in the turn of Thought, and Hand to be seen in Some of the Masters (in Some of their Works especially) that ‘tis the easiest thing in the World to know them at first Sight ; such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarotti, Guilio Romano, Battista Franco, Parmeggiano, Paolo Farinati, Cangiagio, Rubens, Castiglione, and some others ; And in the Divine Raffaelle one often sees such a Transcendent Excellence that cannot be found in any other Man, and assures us this must be the Hand of him who was what Shakespear calls Julius Cæsar. The foremost Man of all the World.

There are several others, who by imitating other Masters, or being of the same School, or from whatsoever other Cause have had such a Resemblance in their Manners as not to be so easily distinguish’d, Timoteo d’Urbino, & Pellegrino da Modena, imitated Raffaelle ; Cæsare da Sesto, Leonardo da Vinci ; Schidone, Lanfranco, and others imitated Corregio ; Titian’s first Manner was a close imitation of that of Giorgione ;

CAMBIASO, Luca

CASTIGLIONE, Francesco

DA VINCI, Leonardo

FARINATI, Paolo

FRANCO, Battista

GIORGIONE (Giorgio da Castelfranco)

IL CORREGGIO (Antonio Allegri)

IL PARMIGIANINO (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola)

MICHELANGELO (Michelangelo Buonarroti)

RAFFAELLO (Raffaello Sanzio)

ROMANO, Giulio

RUBENS, Peter Paul

SHAKESPEARE, William

Conceptual field(s)

There is but one Way to come to the Knowledge of Hands ; And that is To furnish our Minds with as Just, and Compleat Ideas of the Masters (not as Men at large ; but meerly as Painters) as we can : And in proportion as we do Thus we shall be good Connoisseur in This particular.

And as the Description of a Picture is a part of the History of the Master, a Copy, or a Print after such a one may be consider’d as a more Exact, and Perfect Description of it than can be given by Words ; These are of great Advantage, in giving us an Idea of the Manner of Think-of that Master, and this in proportion as such a Print, or Copy happens to be. And there is One Advantage which these have in This matter, which even the Works themselves have not ; And that is, In Those commonly their Other Qualities divert, and divide our Attention, and perhaps Sometimes Byass us in their favour throughout ;

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

His [ndr : Raphaël] first manner when he came out of the School of his Master, was like those of that Age, Stiff, and Dry ; but he soon meliorated his Style by the Strength of his own fine Genius and the fight of the Works of other good Masters of that time, in and about Florence, chiefly of Lionardo da Vinci ; and thus form’d a Second manner with which he went to Rome. Here he Found, or Procur’d whatever might contribute to his Improvement, he saw great Variety of the Precious Remains of Antiquity, and employ’d several good Hands to Design all of that kind in Greece, and elsewhere, as well as in Italy, of which he form’d a Rare Collection : Here he saw the Works of Michelangelo whose Style may be said to be rather Gygantick, than Great, and which abundantly distinguish’d him from all the Masters of that Age ; I kwow it has been disputed whether Raffaele made any Advantage from seeing of the Works of this great Sculptor, Architect, and Painter ; which tho’ ‘twas (I believe) intended as a Compliment to him seems to me to be directly the contrary ; He was too Wise, and too Modest not to serve himself of whatsoever was worthy of his Consideration ; And that he did so in this Case is Evident by a Drawing I have of his Hand, in which One sees plainly the Michelangelo Tast. Not that he rested here, his Noble Mind aspir’d to something beyond what the World had then to shew, And he accomplish’d it in a Style, in which there is such a Judicious Mixture of the Antique, of the Modern Taste, and of Nature, together with his Own Admirable Ideas that it seems impossible that any other could have been so proper for the Works he was to do, and his Own, and Succeeding times.

In Drawings one finds a great Variety, from their being First Thoughts, (which are often very Slight, but Spirituous Scrabbles) or more Advanced, or Finish’d. So some are done one Way, some Another ; a Pen, Chalks, Washes of all Colours ; heightned with White, Wet, or Dry, or not Heightned.

Conceptual field(s)

There are Instances (Lastly) of some whose Manners [ndr : des Maîtres] have been chang’d by some Unlucky Circumstances. Poor Annibale Caracci ! He sunk at once, his great Spirit was subduc’d by the Barbarous Usage of Cardinal Farnese, who for a Work which will be one of the Principal Ornaments of Rome so long as the Palace of that Name remains, which cost that vast Genius many years Incessant Study, and Application, and which he had all possible reason to hope would have been rewarded in such a Manner as to have made him Easy the Remainder of his Life : For This Work that Infamous Ecclesiastick paid him as if he had been an Ordinary Mechanick.

Thus it is evident that to be Good Connoisseurs in Judging of Hands we must extend our Thoughts to all the Parts of the Lives, and to all the Circumstances of the Masters ; to the Various Kinds, and Degrees of Goodness of their Works, and not confine our selves to One Manner only, and a Certain Excellency found only in Some things they have done, upon which Some have form’d their Ideas of those Extraordinary Men, but very Narrow, and Imperfect Ones.

Many Masters have something so Remarkable, and Peculiar that their Manner in General is soon known, and the Best in These Kinds sufficiently appear to be Genuine so that a Young Connoisseur can be in no Doubt concerning Them.

He that would be a Good Connoisseur in Hands must know how to Distinguish Clearly, and Readily, not only betwixt One thing, and Another, but when two Different things nearly Resemble, for This he will very Often have occasion to do, as ‘tis easy to observe by what has been said already.

Expression Connoisseur in Hands Connoisseur en italique

Conceptual field(s)

ALL that is done in Picture is done by Invention ; Or from the Life ; Or from another Picture ; Or Lastly ‘tis a Composition of One, or More of these.

The term Picture I here understand at large as signifying a Painting, Drawing, Graving, &c. [...] We [ndr : présence du déterminant « a » à cet endroit du texte, mais est à supprimer, voir l’errata au début de l’ouvrage] say a Picture is done by the Life as well when the Object represented is a thing Inanimate, as when ‘tis an Animal ; and the work of Art, as well as Nature ; But then for Distinction the term Still-Life is made use of as occasion requires.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

ALL that is done in Picture is done by Invention ; Or from the Life ; Or from another Picture ; Or Lastly ‘tis a Composition of One, or More of these.

The term Picture I here understand at large as signifying a Painting, Drawing, Graving, &c.

Perhaps nothing that is done is Properly, and Strictly Invention, but derived from somthing already seen, tho’ somtimes Compounded, and jumbled into Forms which Nature never produced : These Images laid up in our Minds are the Patterns by which we Work when we do what is said to be done by Invention ; just as when follow Nature before our eyes, the only difference being that in the Latter case these Ideas are fresh taken in, and immediately made use of, in the other they have been reposited there, and are less Clear, and Lively.

So That is said to be done by the Life which is done the thing intended to be represented being set before us, tho’ we neither follow it Intirely, nor intend so to do, but Add, or Retrench by the help of preconceiv’d Ideas of a Beauty, and Perfection we imagine Nature is capable of, tho’ ‘tis Rarely, or Never found.

We [ndr : présence du déterminant « a » à cet endroit du texte, mais est à supprimer, voir l’errata au début de l’ouvrage] say a Picture is done by the Life as well when the Object represented is a thing Inanimate, as when ‘tis an Animal ; and the work of Art, as well as Nature ; But then for Distinction the term Still-Life is made use of as occasion requires.

ALL that is done in Picture is done by Invention ; Or from the Life ; Or from another Picture ; Or Lastly ‘tis a Composition of One, or More of these.

The term Picture I here understand at large as signifying a Painting, Drawing, Graving, &c.

Perhaps nothing that is done is Properly, and Strictly Invention, but derived from somthing already seen, tho’ somtimes Compounded, and jumbled into Forms which Nature never produced : These Images laid up in our Minds are the Patterns by which we Work when we do what is said to be done by Invention ; just as when follow Nature before our eyes, the only difference being that in the Latter case these Ideas are fresh taken in, and immediately made use of, in the other they have been reposited there, and are less Clear, and Lively.

A Copy is the Repetition of a Work already done when the Artist endeavours to follow That ; As he that Works by Invention, or the Life endeavouring to Coppy Nature, seen, or Conceived makes an Original.

Thus not only That is an Original Painting that is done by Invention, or the Life Imediatly ; but That is so too which is done by a Drawing, or Sketch so done ; That Drawing, or Sketch not being Ultimately intended to be followed, but used only as a help towards the better imitation of Nature, whether Present, or Absent.

And tho’ this Drawing, or Sketch is Thus used by Another hand than that by which ‘tis made, what is so done cannot be said to be a Copy ; the Thought indeed is partly borrowed, but the Work is Original.

For the same reason if a Picture be made after Another, and afterwards gone over by Invention, or the Life, not following That, but endeavouring to improve upon it, it Thus become an Original.

But if a Picture, or Drawing be Coppy’d, and the Manner of Handling be imitated, tho’ with some liberty so as not to follow every Stroak, and Touch it ceases not to be a Coppy ; as that is truly a Translation where the Sence is kept tho’ it be not exactly Literal.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)

If a Larger Picture be Coppied tho’ in Little, and what was done in Oyl is imitated with Water-colours, or Crayons, that first Picture being Only endeavour’d to be follow’d as close as possible with Those Materials, and in those Dimentions, This is as Truly a Coppy as if it were done as Large, and in the same Manner as the Original.

There are some Pictures, and Drawings which are neither Coppies, nor Originals, as being partly One, and partly t’other. If in a History, or large Composition, or even a Single Figure, a Face, or more is incerted, Coppied from what has been done from the Life, such Picture is not intirely Original. Neither is that So, nor Intirely Coppy where the Whole Thought is taken, but the Manner of the Coppier used as to the Colouring, and Handling. A Coppy Retouch’d in Some places by Invention, or the Life is of this Æquivocal kind. I have several Drawings first coppied after Old Masters (Guilio Romano for example,) and then Heightned, and endeavour’d to be improved by Rubens ; So far as His hand has gone is therefore Original, the rest remains pure Coppy. But when he has thus wrought upon Original Drawings (of which I have also many Instances,) the Drawing looses not its first Denomination, ‘tis an Original still, made by two several Masters.

The Ideas of Better, and Worse are generally attached to the Terms Original, and Coppy ; and that with good reason ; not only because Coppies are usually made by Inferiour Hands ; but because tho’ he that makees the Coppy is as Good, or even a Better Master than he that made the Original whatever may happen Rarely, and by Accident, Ordinarily the Coppy will fall short : Our Hands cannot reach what our Minds have conceiv’d ; ‘tis God alone whose works answer to his Ideas. In making an Original our Ideas are taken from Nature ; which the Works of Art cannot equal : When we Coppy ‘tis these Defective Works of Art we take our Ideas from ; Those are the utmost we endeavour to arrive at ; and these lower Ideas too our Hands fail of executing perfectly : An Original is the Eccho of the Voice of Nature, a Coppy is the Eccho of that Eccho.

Conceptual field(s)

Conceptual field(s)